The search spiders we send out to crawl the web in search of information about the Basques usually come back loaded with news, collecting publications of all different types that speak about the Basques from sources all over the world. But they also sometimes bring us reports that were published a while ago, such as this one about the history of Basque whalers in Iceland.

The article in question was written by Wendy Zeldin and was shared by Francisco Macías at In Custodia Legis, the official blog of the US Library of Congress. Both work at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, and Francisco Macías regularly contributes to the blog.

This entry was written in June of 2015 upon the repeal of a law decreed by Ari Magnússon, the sheriff of the Western Fjords, in the northwest of Iceland, in 1615. This law was in force, though unenforced, until April 2015, and we even blogged about it and its repeal at that time.

It’s quite interesting to us that this Library of Congress blog dedicated an entry to this legal curiosity: this permission to “kill Basques” was technically in force for around 400 years.

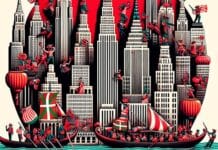

The article tells of the conflict that arose in the winter of 1615, which ended with the deaths of 32 Basque whalers at the hands of the Icelanders who lived in the region of the Western Fjords. This turns out to be the wildest part of the island, at least back then, and it was severely affected by a series of bad harvests.

At the end of the whaling season, with winter approaching, three Basque whaling ships sank in a storm off the coast of Iceland, and some 83 sailors needed local resources to survive the winter there, and they found themselves competing with the local residents. This gave rise to confrontations, and a persecution that ended up with locals killing 32 of the Basques in a terribly barbaric way. The description of the murders is known thanks to a tal written by Jón Guðmundsson the Learned called “A true account of a Spanish shipwreck and battle” (Sönn frásaga af spanskra mann skipbroti og slagi).

What followed afterwards makes us believe that things went back to normal, despite the fact that the decree was never repealed. This is evidenced by the creation of a Basque-Icelandic pidgin which was created by locals and whalers, and even written down by Icelandic erudite Jóns Ólafssonar úr Grunnavík. We’ve spoken about this exchange language before.

In that article, we covered a document titled “Vocabla Biscaina” which was one of the names given to the Basque language at the time. There’s yet another glossary, titled “Vocabla Gallica“, which might lead us to believe that it refers to French, but it turns out that it is also a Basque-Icelandic glossary. Both documents can be found on the website of The Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies (in Icelandic). Both short, 17th-century handwritten dictionaries were made public in 1937 by Dutch linguist Nicolaas Deen, in his doctoral thesis, Glossaria duo Vasco-lslandica.

Also relevant to all this is that a good part of the terms in Basque belong to the Labourd dialect, so we can deduce a significant part of the Basque whalers came from that part of the Northern Basque Country; this despite the fact that the three ships that were sunk had come from San Sebastian.

This constant difficulty for Basques on either side of the Pyrenees to be recognized as one people isn’t only found in these two dictionaries. We can also find that Thomas Jefferson wrote about cod fishing and whaling on February 1, 1979, which we cite below:

“The whale fishery was first brought into notice of the southern nations of Europe, in the fifteenth century, by the same Biscayans and Basques, who led the way to the fishery of Newfoundland.”

It seems quite evident that when Jefferson refers to the “Biscayans,” he is referring to those living south of the Pyrenees, which the “Basques” live north of them. Both are the same culture and speak the same language (as can be seen in the glossaries), but as they are divided up by two kingdoms, they are identified separately.

We’ll leave you with Wendy Zeldin‘s post on the official Blog of the UN Law Library of Congress.

There is also this .pdf file about this story, found on the website prepared in Iceland when this law was repealed in 2015

IN CUSTODIA LEGIS – 17/6/2015 – USA

It’s No Longer Open Season on the Basque in Iceland

Having recently watched several episodes of The Eagle, whose protagonist is a troubled but brilliant Icelandic detective working in Denmark, and having followed the exploits of Arnaldur Indridason’s Detective Erlendur, I consider myself no stranger to Nordic criminal justice, at least from a fictional perspective. However, I was unaware of some of the dark deeds in 17th century Iceland, until I recently learned about the symbolic righting of an old wrong.

(Follow) (Automatic translation)

Foto de cabecera: Mapa de Islandia, Abraham Ortelius 1587. Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Last Updated on Dec 3, 2023 by About Basque Country