This article was translated by Joseba Varela

In this day and age, certain voices are casting doubt on which territories actually conform the Basque homeland in the Iberian Peninsula. At least since the 1970s, we have suffered from a trend of historical revisionism rejecting the notion that Navarre is part of that homeland. The efforts aimed at writing a history of the peninsular Basques that suits the taste of Spanish unionism, which have been well rewarded by the Spanish centers of power, have created a discourse that has often bordered on the absurd.

A discourse that goes as far as to claim that, on the one hand, Navarrese people are not Basque, while suggesting on the other that the territories that now make up the Basque Autonomous Community (CAPV) were populated by other groups and were later forcibly taken by the Basques. Therefore, we can’t help but ask ourselves the following question: if the Navarrese people are not Basque, as they claim, where did the Basques that now live in the CAPV come from?

Fortunately, in spite of the continuous rewriting of history, there are still glimmers of truth; Peruvian international adviser Carlos Jara’s article for the Alfanoticias website is a good example of that.

The article analyses a trade mission sponsored by the Diputación Foral de Bizkaia (Biscayan Regional Council) to the aforementioned country, something that would already merit a mention in our own website, but which won’t be the focus of this article due to some other information included in Mr Jara’s article.

The reason why is very clear. Judge it yourselves:

Peruvian Francisco Igartua Rovira, of Basque origin and born in Huarochiri, now part of the Lima province, stated in the First Congress of Basque Communities, held in Vitoria in November 1995, that, contrary to what is widely believed, the first Basque centre in America wasn’t founded in Montevideo (1876), but in Lima at the beginning of the XVIIth century, as shown in the bylaws of the “Distinguished Brotherhood of Our Lady of Aranzazu”, founded by the “gentle noblemen that reside in this City of the Kings of Peru, originally from the Lordship of Biscay and the Province of Gipuzkoa, as well as those from the Province of Alava, the Kingdom of Navarre and the four Villages on the coast of the Mountain… in the Convent of Saint Francis of this City, in the chapel devoted to the Holy Christ and Our Lady of Aranzazu, which was initiated in 1612…

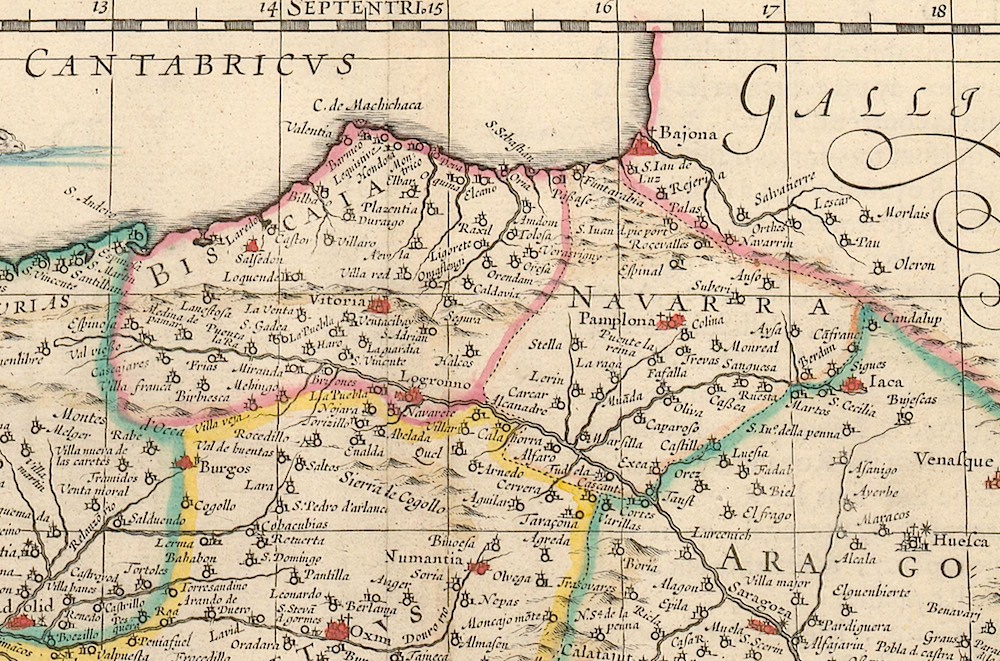

There are no words that can better express what Basques were and are. It cannot be denied that, according to the Basques of the XVIIth century, peninsular Basques were those mentioned in that description, including the villages of San Vicente de la Barquera, Santander, Laredo and Castro Urdiales, which, whilst not being part of the Basque Homeland, maintained such a tight economic bond with the towns of the Basque coast that they were sometimes presented as part of Biscay in the contemporary maps. These villages later followed a different path, until they ended up being part of what is currently known as Cantabria.

That took place at the beginning of the XVIIth century. Yet, what happened almost 300 years later, in the first half of of the XXth century? It seems things hadn’t changed much. In 1903 and as a result of popular subscription, the Navarrese people built a monument to their Code of Laws (Fueros) in downtown Pamplona. As we can see in the plaques of such monument, the Navarrese Basques of that time made clear their principles and sense of belonging. Of the five plaques, two are very explicit in that regard:

“GU GAURKO EUSKALDUNOK GURE AITASOEN ILLEZKORREN OROIPENEAN, BILDU GERA EMEN GURE LEGEA GORDE NAI DEGULA ERAKUSTEKO”. (“We, the Basques of today, have gathered in this place in immortal remembrance of our ancestors, to demonstrate that we want to preserve our Law.”)

“GU EUSKALDUNOK BESTE JAUN EZTEGU JAUNGOIKOA BAIZIK, ATZEKOARI OSTATUA EMATEN DEGU ONIRIZKERO BAINO EZTEGU NAI AIEN UZTARRIA JAZAN. ADITU EZAZUE ONDO, GURE SEMEAK”. ( “We the Basques have no other lord than God. To the foreigner we dispense warm hospitality, yet we don’t want to be under their yoke. Listen carefully, sons of ours”.)

We may be wrong and the monument could have been erected in defence of the views of just a part of the Navarrese people, those who already adhered to the then-recently born Basque Nationalist movement. Something that is totally opposed to how reality actually was, but let’s accept it as a possibility. It was a time when many things were happening in Navarre, and all of them, at least those defending Navarrese Freedoms, were done hand in hand with the rest of the Basques.

What therefore did the inhabitants of those territories that in 1936 supported the military coup against the Government of the Republic think about this subject? A coup that instigated by an insurgent movement led by a specific vision around the defence of the “unity of the Spanish Homeland” and that was followed by a dictatorship that was defined by its idea of Spain as “One, Great and Free”.

There is nothing more explicit regarding what they thought about the Basque peninsular homeland and, consequently, of who the peninsular Basques were, than their own, first public demonstrations, which were imbued with the greatest of enthusiasms and ideological fervour.

For that purpose, let’s select a Gipuzkoan newspaper, El Diario Vasco. A paper that is described in Wikipedia in the following way:

El Diario Vasco is a paid-for newspaper that is published in Gipuzkoa, Spain. It was founded in November 27, 1934 by the Basque Society of Publications (Sociedad Vascongada de Publicaciones), Pedro Pujol being its first director. Among its founders, there were contemporary conservative politicians such as Ramiro de Maeztu or Juan Ignacio Luca de Tena.

Despite being bilingual in Spanish and Basque, 90% of its news were published in Spanish. When the coup d’etat that led to the Civil War took place, El Diario Vasco supported the rebels- not for nothing, banker Juan March was its owner-and was closed down by the Republican government. After Donostia was conquered by the francoist troops, El Diario Vasco again came into circulation.

Let’s head towards those first moments when the journal was re-published after the occupation of Donostia by the insurgents, and take a look at the masthead of its May 2, 1937 edition. In other words, a number published just a few days after the Bombardment of Gernika, which took place in April 26, 1937.

Please, do pay attention to the masthead. Right. On the left of the diary’s name, there’s a coat of arms. It is a “Laurac-bat”, the emblem that represents the peninsular Basque territories: Araba, Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa and Navarre. This newspaper was published by the most rabid anti-Basque nationalist individuals, so there’s little doubt that they regarded the inhabitants of these four territories, in spite of also considering them “Spanish from top to bottom”, as the true and authentic Basques.

Please, do pay attention to the masthead. Right. On the left of the diary’s name, there’s a coat of arms. It is a “Laurac-bat”, the emblem that represents the peninsular Basque territories: Araba, Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa and Navarre. This newspaper was published by the most rabid anti-Basque nationalist individuals, so there’s little doubt that they regarded the inhabitants of these four territories, in spite of also considering them “Spanish from top to bottom”, as the true and authentic Basques.

Therefore, what has happened since the end of the dictatorship to nowadays for such a reality-distorting process to have taken place? There will surely be all kinds of explanations. But, in our opinion, there are two main reasons behind the effort to “de-Basquisize” the Navarrese people.

The first one, the desire of the “beaumontoise” right-wing in Navarre to preserve the power over the economic and political structures they possess since the Castilian invasion at the beginning of the XVIth century.

The other one is related to the fear of those very same social, political and economic groups towards the possibility that the theses of Basque nationalism could ever penetrate Navarre, something that happened, rather intensely, before the Civil War. The military upheaval effectively “purged” Navarre from those ideas, be it by burying them in the common graves where people that held them ended up after being killed by the insurgents, or be it by watching them go to exile with those who managed to escape.

We can attest how hundreds of books and articles, as well as unionist historians and politicians, claim that the Navarrese are not Basque. But the Truth is just like water, it filters through all the cracks and eventually soaks everything.

We leave here the article that has led to this whole reflection. A fascinating text full of interesting references, to whose author we cannot help but be thankful.

Alfanoticias – 5/4/2014 – Peru

VISITAN AL PERU REPRESENTANTES POLITICOS Y COMERCIALES DEL PAIS VASCO

En una larga conversación con nuestro profesor de Historia del Derecho Juan Vicente Ugarte del Pino en Madrid, alla por los años de 1990 cuando en el mes de junio llegaba a instalarse en la Residencia del Colegio Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe en Madrid, para dictar su Curso de Derecho Comparado en la Universidad Complutense Madrid, nos relataba mientras desayunábamos con el en la cafetería de la residencia pasajes de la historia de España y recuerdo haber conversado de forma distendida sobre los Vascos en el Perú de esas conversaciones guardo muchos recuerdos de nuestro maestro.

(Continue) (Automatic translation)

This entry is no longer available in the Alfanoticias website. Fortunately, Emprebask Perú has kept it and we can consult it in their website.

Last Updated on Sep 5, 2022 by About Basque Country