Cabanillas, Cadreita and Carcastillo

Cabanillas

The land was still the most pressing problem in the Municipal Elections of April 1931. Once again, the left contested the elections, and the right maintained the majority, this time with three councilmen from the UGT labor union inside the council. In 1933, the lands were symbolically occupied, and would be cleared out by the Civil Guard. In 1935, the tention about the land increased, the corralizas were still full, and 80 members of UGT started to break them. The Civil Guard was in attendance at the council meetings.

July 18 brought the first measure to remove the three left-wing councilmen, and Valentín Cervera, upon raising his fist at the requetés trucks as the passed, was shot and injured, though he escaped. On August 3, nine people were arrested, including Luis Aguado, a father of six, one of whom, Pedro, was also arrested. In that group we can also find Teófilo Julio Cervera, Julián Paz, Macario Marín, Manuel Jimeno, Luis Pérez Galindo, and brothers Pascual and Gregorio Pérez, who managed to escape being shot by kicking one of their hangmen in the leg. They tried to pick up Pascual Pérez when they discovered he’d gone to a hospital to have an injury treated; he was shot as he left the Tudela medical center. Gregorio Pérez, the other brother, would go into hiding, in his home, for the next ten years.

Felisa Aguado, aged 64, and her daughter Simona, 19, of a Communist family, had their hair cut. Simona, the daughter, was repeatedly raped at the Cabanillas jail. Her pleas for help could be heard from the street, and from the home of Parish Priest Carlos, who lived right in front: “No more! No more!” They were shot in Valtierra, in the truck that was also carrying two of Simona’s brothers, one aged 14, who was saved by the Parish Priest at the last moment, and anther named Proceso, who was shot on Tudela Bridge, injured, and then disappeared.

Santiago Pérez was also shot when he went in search of his dead son, and Leoncio Serrano was shot in Castellón after being reported by some of the townsfolk. The repression continued for years, as residents were subjected to forced labor, insults, fines, and confiscation of goods. All the reports against leftist residents and their families were sustained by their not going to church and their not being part of the National Movement.

Cadreita

To speak of Cadreita is to speak of feudalism. It is to speak of Miguel Osorio, Grandee of Spain, Duke of Alburquerque, of 30,500 robadas (2.74 ha, 6.77 acres) of land, of houses inhabited by colonists on his property. When the Republic arrived, the Republican-Socialist Coalition won out, followed by the Republican Center sending a letter to the acting Prime Minister, which summarized the majority feeling in that Town of 1,300 in 1930, requesting that the lands be divided up: “we have never gotten out from under the control of a feudal lord who rules our lives and homes, but not our consciousness, which was free to express itself on April 12.”

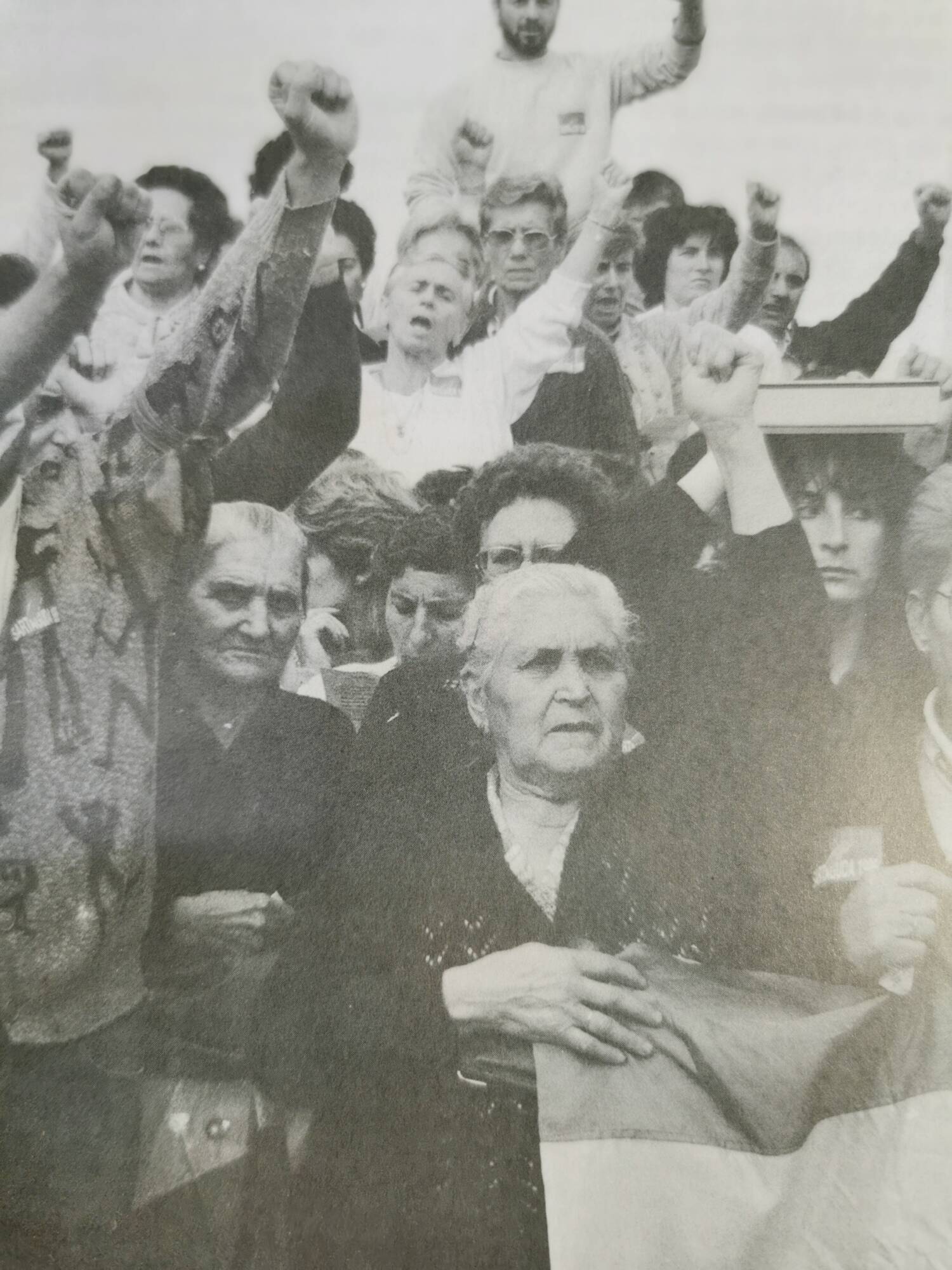

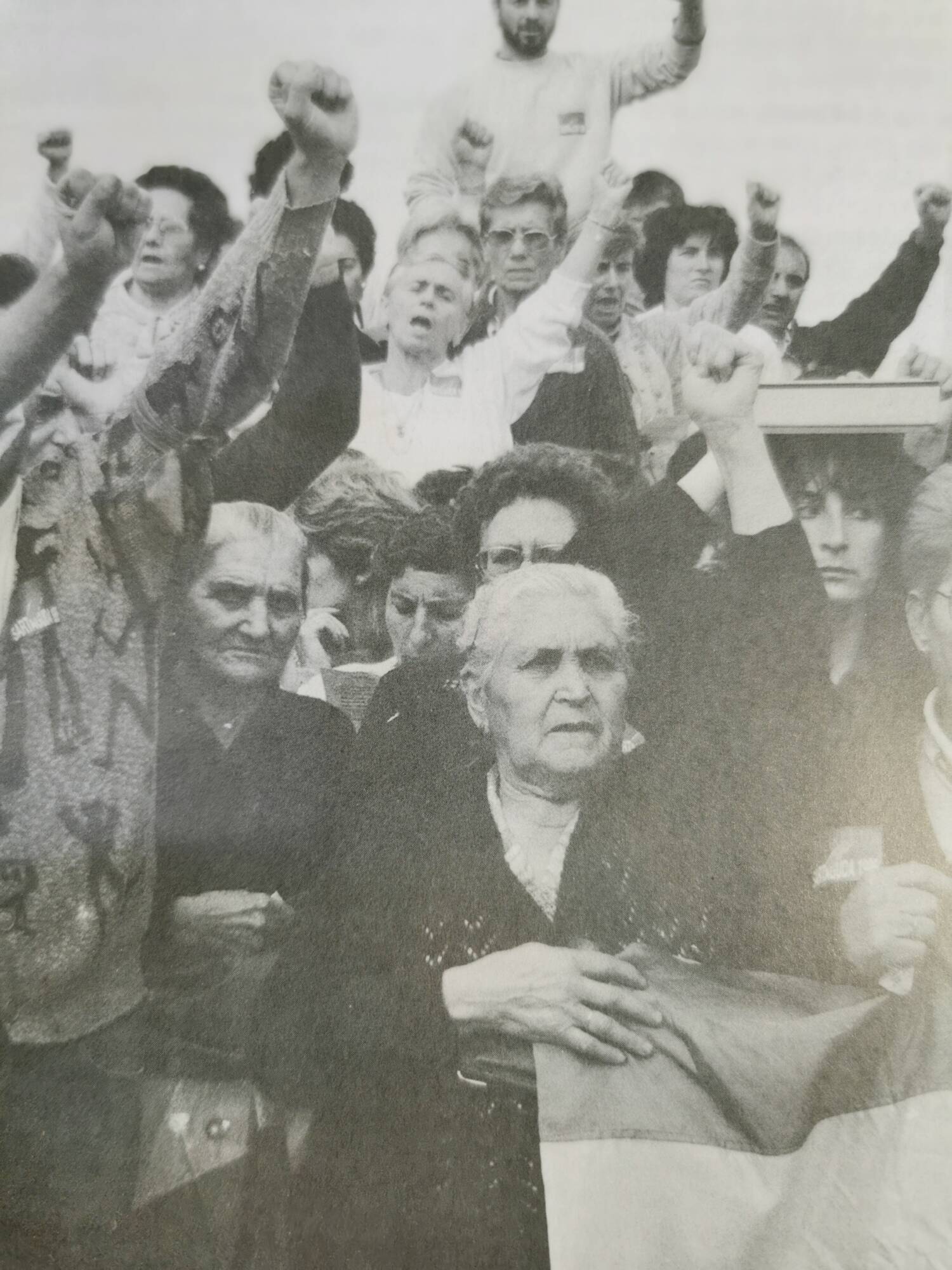

In Cadreita, unlike the rest of the Lower Ribera region, the murders took a few months to arrive. They started with cutting the hair of Presentación Preciado, Beatriz Rubio, Felipa León, Julia Martínez…but they did not make them drink castor oil. They turned of leftist families’ water when it was their time to water their land, their women were insulted, and the men were forced to work with horses, and to work for free on the fields of those on the right; their property and animals were taken away.

The first murders were of those who had been forced to sign up for the Sanjurgo Corps, six young townsmen shot in Zaragoza in October 1936: Marcelino Cambra, Julián León, José Ochoa, Emiliano Pérez, Nicolás Preciado, and Pedro Preciado. Mayor Cipriano “Rojillo” Sánchez went into hiding in the Bardenas. There, he met his newborn son when he was being brought food and water. He was discovered in October and shot in Balsa El Rey.

On November 12, eleven townsmen were taken out of Tudela jail “to set them free”, and were then shot that night on the Balsaforada city limits. They were former mayor Benito Burgaleta; Mauro Alio, laborer; Modesto Esparza; Eusebio Jiménez; Galo Oscoz, father of six; Ciriaco Pejenaute, councilmen, who was ill when he was taken from his home; Tomas Pérez; brothers Ángel and Antonio Sánchez; and Ángel Prat.

Four days later, in a raid in the Town, Sabino López, father of eight; Luis León; José Vicioso and his brother Pio; Alejandro Oscoz; Julián Torres; Micaela Ochoa, mother of six; Santiago Ochoa, father of five; Segundo Montes; and León Sabanza were all taken away…and shot.

Some townsfolk escaped to the Bardenas; they were chased and killed, and so far, their bodies have never been found. The widows and orphans suffered the Francoist repression for decades. Vicenta Cambra, the widow of Alejandro Oscoz, was evicted from her home. The Civil Guard visited leftist women who were not attending church. One of them replied, “I’ve always gone, but until my hair grows back and my husband is buried in holy ground, I will not return.”

Carcastillo

In a town of 107,100 robadas (9600 ha, 23,800 acres), there were 300 unemployed people in 1932. The Monks at the Oliva Monastery fed many of the children of poor families every day. The Parish Priest of Carcastillo preached one Christmas to the rich that enough was enough with huge feasts while other families were going hungry.

The repression in Carcastillo was held in check in part thanks to the attitude of the priest, Jacinto Argaya, and some other influential locals on the right. On October 12, 1936, a truck came from Pamplona ready to carry out a raid on the Town’s reds to take them to be shot, but thanks to the locals’ influence, in the end they were taken to San Cristóbal Prison. During that raid, practitioner Celedonio Ramírez was at the home of a patient. When he found out they were coming for him, he hid in a corral until the truck drove away with the prisoners.

By that time, a caretaker from Sangüesa; two day laborers from Caseda who had sought refuge in Carcastilloa; and a Carcastillo businessman, Justo Sopeña, who returned to his hometown of Calahorra seeking refuge, had all been arrested and shot. Other nationalists and leftists were “volunteered” for the Sanjurgo Corps, and were shot in Zaragoza: brothers Blas and Guillermo Pérez; their cousing Cipriano Pérez; Ricardo Abadía; Eladio Pérez; Florentino Viloche; Matías Sanz, aged 19. Others were signed up and died on the front: Nemesio Alfaro, Rafael Colas, Antonio Alfaro, and Felipe Remón, president of the Basque Nationalist Party in Carcastillo.

The environment of terror and repression was the same in other towns in La Ribera and throughout Navarre. Six women had their hair shaved off in the Main Square, and the insults were constant against republicans, socialists, and Basque Nationalists; this last group had been a major political force in Carcastillo. Their houses were raided and pillaged, taking animals, cereals, vegetables, and money, and several families were kicked out of town. Altafailla Kultur Taldea, in their book “Navarra, de la esperanza al terror”, the basis for these articles, makes special mention of Leopoldo Calvo.

Leopoldo Calvo was 17 when he was taken to the San Cristóbal Prison, where the abuse caused him to lose his sanity. He had to spend the rest of his life in a psychiatric hospital, where he passed away at the age of 80.

On Monday, a group from Tudela on social media started making personal attacks based on the publication of the first entry in this series. That was to be expected, but seeing as how they will surely not only attack me personally but also the source, in this case the book “Navarra, de la esperanza al terror, 1936”, I would like to also add some testimony written in an Ecclesiastical Archive called “The Gomá File”.

This File is a series of thirteen volumes published by the High Center for Scientific Research between 2001 and 2010, and is basically made up of documents regarding the fascist uprising and its relationship with the Catholic Church. The name of the File comes from Cardinal Isidro Gomá Tomá, born in the Catalan city of Riba in 1869.

This Catalan priest became Bishop of Tarazona in 1927, and Archbishop of Toledo and Primate of Spain in 1933, and Cardinal and Nuncio of Spain in 1935, meaning he was Franco’s ambassador to the Holy See and Pope Pius XII until his death in 1940.

Gomá traveled to Navarre, specifically between 1936 and 1939, and there is infinite correspondence collected in his personal archives; sufficient documentation to have exhaustive knowledge of what happened, precisely due to the manuscripts found herein, and especially because the material can’t be dismissed as “red” or “separatist”. We’re talking about the correspondence of a Francoist Cardinal.

Among the letters is one dated January 1937, when the Vicar of the Diocese of Vitoria, Antonio María Pérez Ormazábal (who had been named to control the nationalist clergy, after the expulsion of Monsignor Múgica) describes the situation to Cardinal Gomá: “Nor is it true that the priests that have been marked have ever carried out nationalism in the towns… What priest could be proven to have carried out Basque nationalist politics, either from the pulpit or anywhere else? They were prohibited from attending rallies, batzokis, etc. and they obeyed… To finish off nationalism, a different procedure must be followed: do not persecute the priests, do not persecute the language, do not confiscate so many goods, do not impose so many fines, do not take priests and peasants to their deaths only because they’re nationalist.”

Last Updated on Jan 16, 2021 by About Basque Country