Milagro

On the lands of José Sánchez Marco, the largest landowner, 30 families worked 11 hours a day for 3 pesetas, when the normal salary paid in the area was 5.5 pesetas, or even 6. Hunger was a reality, not a mirage, and in many cases there were no real homes, just caves to be inhabited.

By the 1920s, Milagro had a population of around 3,000, and there was a Resistance Society for Different Trades called Aurora Social. In 1930, the local UGT labor union chapter was set up. In the April 12 elections, the right once again was victorious, over the protestations of the left. The City government was not set up until June 27, when two leftist councilmen managed to get seats. Milagro would vote in favor of the Estella Basque Statute of Autonomy on June 19, 1932. In those days, the Navarrese right felt themselves to be a part of the same destiny as their sister Basque provinces, and as some would say now, to be a good Navarrese was to feel Basque.

Socialists and leftists in general suffered continuous attacks from the Civil Guard, as well as being discriminated against when being called for work; going hungry, and having to deal with all the messages of fire and brimstone from the pulpit against the Republic and its leaders. Social tension was constant, and in the years prior to the fascist military coup, the left suffered continuous reprisals. But the worst was yet to come.

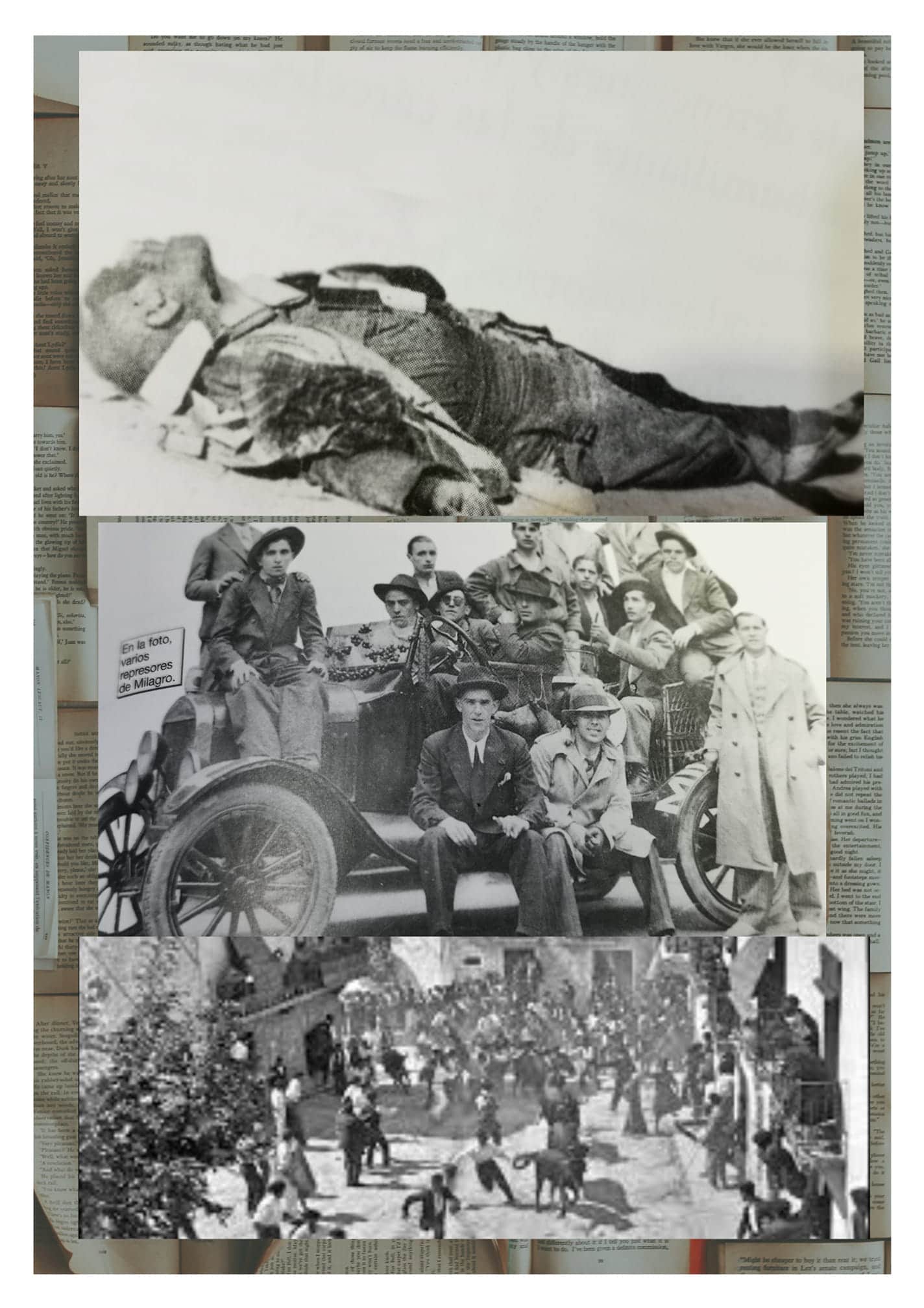

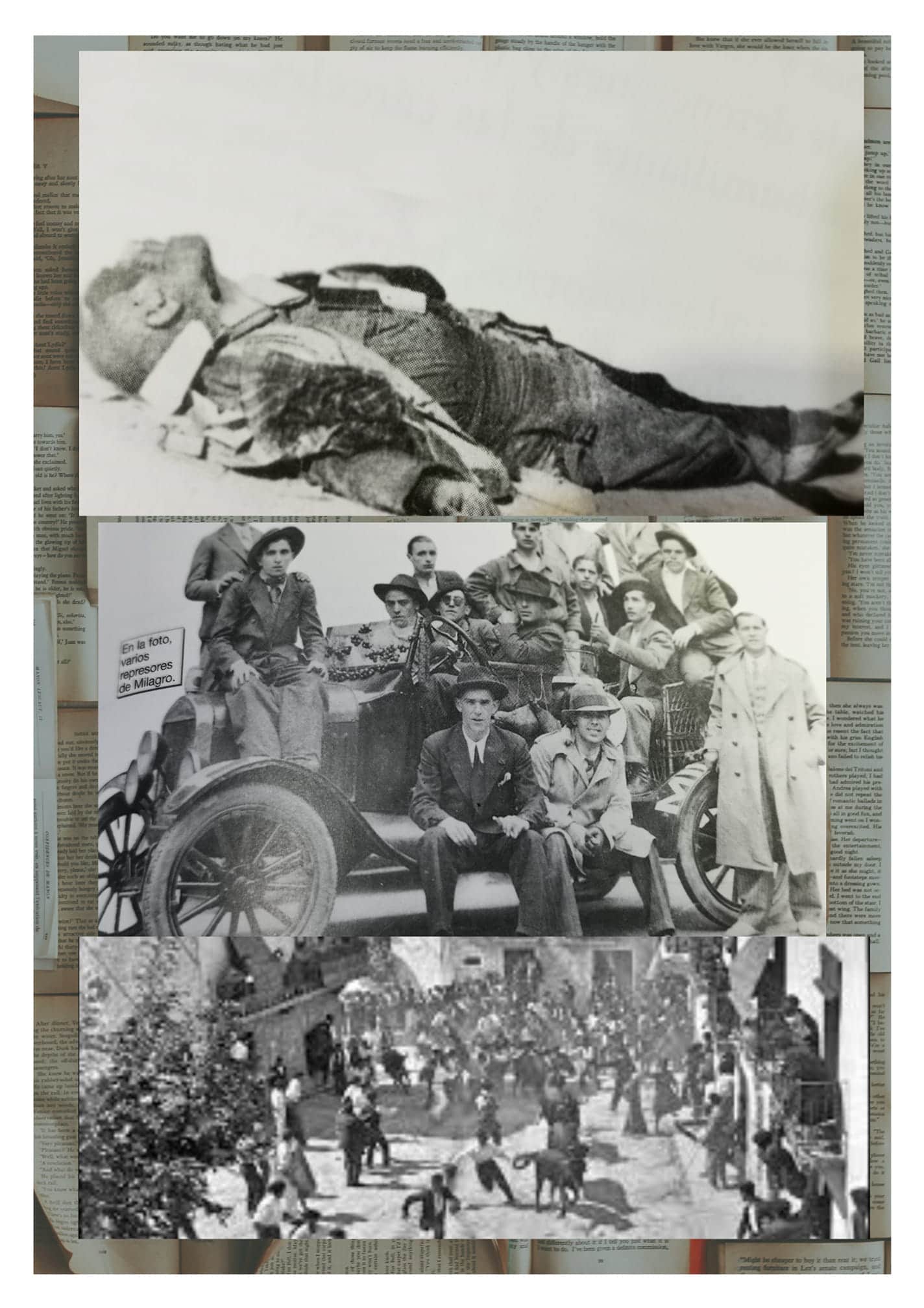

When news of the fascist military uprising against the legally constituted régime of the Republic reached Milagro, many townspeople fled to the fields. On July 22, José María García, a 31-year-old dayworker, was thrown off the San Miguel outcrop and landed on the rocks, and spent the whole day there, suffering, unaided, stoned by schoolchildren who had been encouraged by their teacher. Finally, a Civil Guard and another finished him off from the shore.

The next day at the Sol Mayor, young Felipe Díaz, a 23-year-old who worked at the water mill and was about to get married, was killed. Postman Vicente Pardo, Apolonio Antón, Francisco Preciado, Emilio Hernández, Ponciano Martínez, Francisco Pejenaute, and Antonio Ochoa were killed in Lerin; the last one, according to some sources, was sliced through the belly in the City Hall porch, and walked, holding in his guts, to where the gas station is today, where he fell down dead.

On July 25, the day of the patron saint of Spain, 35 men are transported to Pamplona prison, and several of them were killed, including José María Lebrero, whose eyes were gouged out after he was shot down, and then thrown into the river. His body turned up at the “Hormiguero” in Alfaro. He left behind a widow and eight small children. Marcos Estañan, the smith, died in bed, and not due to disease. His murderers went to the hospital where he was being treated and shot him there. He had seven children, and it’s been said they’d meant to bury him alive. On the day of St. James, they also killed Cornelio Las Peñas, Agustín López-Bailo, Jesús Luquin, Jesús Los Arcos, Cándido Diago, José Salvador Ibáñez, Jesús García, Felipe Gollarte, and Segundo Oscoz, who left behind four children with handicaps. Simón Pejenaute was killed in Fitero.

On August 5, 25 townsmen were taken out of the jails and killed in Venta de Arlas. They were: Inocencio Aguerrí, Félix Broca, Leandro Carrascón, Cándido Évora, Francisco García, and barber José García, who was made to serve as a step so the rest could jump on him; his white coat was found among the remains. Ricardo Pejenaute refused to jump, so he was tied up and dragged behind a truck until he died. They also killed Constantino Garde, Andrés Ibáñez, Diego López, brothers José Donato and Valentín López Ochoa, José López, Federico López-Bailo, Manuel Antonio Los Arcos, Jesús Martínez, Gregorio Martínez Ruiz, Ernesto Nantes, Nicolás Pejenaute Bayona, Ricardo Pejenaute Évora, Félix Pérez, Gregorio Preciado, Marcelino Ruiz, Francisco San Emeterio, and Vicente Salvatierra.

León Lebrero, aged 60, who came back from watering with his donkey, was killed and buried among the beets on August 22. The dogs dug him out soon after. Before the end of August, Dionisio Azona, originally from Villafranca and a resident in Milagro, would be killed in Pamplona. The enthronement of the crucifixes in the schools was celebrated on August 30 with a mass in the Square of the Charters. It was full of requetés, falangistas, margaritas, Civil Guards, and other authorities. The Mass was held with Marclino Azpiroz as coadjutor, doctor Antonio Moreno as the acolyte, and local Carlist Committee chairman Esteban Saralegui as the collector. They were all key players in the repression of Milagro.

Ceferino Preciado and Modesto Pardo were killed in September; the latter, according to several testimonies, was half-buried and then beaten. Simón Hernández was found in October in Zaragoza, where he had taken refuge with some relatives; he was killed right there. Thirteen men were taken out of jail on October 7 and taken to Peralta, where they were killed: Ángel Aguerrí, Pedro Arriazu, Ángel Barrado, Miguel Escalada, Pedro Garde, Eugenio Gollarte, Jacinto Hernández, Juan Lafraga, Juan Martínez, Dimas Pejenaute, Isidro Ruiz, Evaristo Vidal, and Luis Pardo, who was taken out in a chair as he was too sick to walk.

There was another trip to Peralta on October 17 to kill José Abad, Remigio Lebrero, Alejandro Navarro, Julio Osma, Alejandro Pejenaute, and Nicolás Matías Ruiz, who was married to Ángeles Sesma, who was just about to give birth. She requested they leave him one more day. They refused, and she gave birth to a girl the next day. Julio “El Remolachero” Sánchez, Andalusian by birth, had his house stoned and sacked: they took his furniture, paintings, and silverware. They also beat him out, tied a noose around him, and dragged him through the gutters. They took him to San Martín de Unx, and on the border with Ilagares, they shot him. His family was expelled from the town and had to beg to survive.

In 1937, some others were also killed, and the arrests did not stop. Leftist homes were stoned. Suspects were made to wear white bracelets, even women and children. The widows of those murdered were humiliated and locked away in storerooms since the jail was full. Their hair was cut and they were forced to walk through the town. They were then taken to the bullring to fight, depending on their ages: the young ones were “heifers” and the others “old cows”. They sacked houses at gunpoint, stole land and property, and fined the families of those who were killed and those few who managed to survive.

On May 23, 1937, Isidoro Torrecilla, Rufino Rodero, Serapio Lebrero, and Pablo Barco were shot in Pamplona. They also shot Antonio León and Carmelo Centro in Aldea Nueva de Ebro and Daniel Pérez in Moncayo.

In just a few months, more than 80 men were killed in Milagro, and that’s not including those who were forced to join the fighting and died on the front, the ten who disappeared, and deaths that were suspicious, including parish priest Victoriano Aranguren, who had asked for clemency from the murderers on many occasions. Jesús Salvatierra managed to escape in an alfalfa truck across the border. An anarchist, he was at the front in Madrid and ended up in a concentration camp in France. As of the latest printing of “Navarra, de la esperanza al terror, 1936”, he was still alive.

Testimony of J. L. from Milagro, in “Navarra, de la esperanza al terror 1936”

Hair cuts

“I was the first. The jail was full and that’s where they put us, in the jail upstairs, in the grain storerooms of the jail is where they put the women. There were some small windows there overlooking the plaza. There was the Cope, the casino of those on the right. And the whole town in the plaza waiting for us to come out. From above, from the small windows, waiting our turn, unable to look out because we couldn’t, we kept hearing them waiting for us, ‘Kill them, kill them’, and they said, ‘What do you want, old or young?’ The young ones were called ‘heifers’ and the ladies ‘old cows.’ That was the plaza where they held bullfights. Next to the church, where it says “Workers’ Cooperative”, in front of the City Hall, that’s where they did all these things. From the windows we could hear they were waiting for us to fight, the whole town waiting for us.”

“Let us be men and let us know how to avenge the fallen, even if it means putting the socialists in mourning in their centers for a year. Because against those, any procedure is good: the bomb, the fist, and the fire.”

(Jaime del Burgo, April 1934, in the journal of the Traditionalist School Association)

Last Updated on Jan 16, 2021 by About Basque Country