This article was translated by John R. Bopp

The peoples who don’t usually write their history, because it’s usually written for them (by the victors in a confrontation) suffer, along with the loss of their freedoms, some extra punishments. Among them, the fact that the children of their land who become famous stop being their children to become the children of the land that has subjugated them. We Basques know a lot about that, when we see our protagonists in History turned into Frenchmen or Spaniards in books: Basques who defined themselves as such, directly and positively, still appear in history books as members of a community they did not identify with.

Speaking of that always brings to mind, as a paradigm of this usurpation, the case of José de Anchieta, the most important missionary in Brazil and the founder of Sao Paulo. His résumé is infinite: nurse, scientist, linguist, author, founder of cities…a true Renaissance man. All his biographies mention how he was beatified; he was the son of a Gipuzkoan from Urrestilla, who had been exiled to the recently conquered island of Tenerife for supporting the Comuneros in the Revolt of the Comuneros; he was related to Saint Ignatius of Loyola (another Gipuzkoan); he became a Jesuit; he was missionary to Brazil; he was a Spaniard born in La Laguna on Tenerife Island in the Canaries. All this is true, but being born on Tenerife in 1534 (less than forty years after its conquest) does not make one a Canary Islander, just as being born in Cuba in 1550 (forty years after its conquest) does not make anyone Cuban. What all his biographers seem to forget, however, is that after being a leader of the Jesuits in Brazil, after having been born in La Laguna, after having studied in Portugal, after having spent his whole life serving the King of Portugal in the colonization of Brazil, after all that, he still, in a letter he sent to the Company of Jesus, defined himself as…Biscayne (a common adjective for all Basques of the time). What’s sad is that not even we Basques recognize him as one of ours, because we don’t know his history, thanks to the fact that others have taken care (and still do) of writing it in their own way.

Well, something similar happens with Maurice Ravel. His birth in Ziburu/Ciboure is either not known or only given an anecdotal value of little import, and which has no bearing on the career of this incredible French composer. Few discover he spoke Basque. What’s more, they say his mother was Basque, but descendent from an old Spanish family, as if being Basque always had to be subrogated to something superior, being either Spanish or French. At most, they may wonder what influence the popular Basque music his mother sang to him in his childhood could have on his career, always while reminding that he didn’t revisit his homeland until he was 25.

Few speak about his unfinished work, a grand piece titled “Zazpiak Bat (From Seven, One)”, dedicated to the Basques, which he abandoned with the start of the First World War. But the work he did for that piece left its mark on others of the composer’s works, such as his Trio for Piano, Violin, and Cello in A Minor, where we can find notable influences of traditional Basque music.

And this is where we get to the crux of the matter. The “Zazpiak Bat” coat of arms and motto were created at the end of the 19th century to call for the union of all the Basque territories. They were created in the Northern (or French) Basque Country in 1897, when Ravel was 22, and reflects a social and political movement with a wide base, looking to recover the Basque rights and freedoms which had been lost in the French Revolution north of the Pyrenees and in the Carlist Wars south of them.

From our point of view, choosing this exact title for his work clearly indicates the composer wasn’t looking to simple pay homage to the land of his childhood. The title of any work of art looks to represent the spirit contained therein, and using the term, and idea, of “Zazpiak Bat” goes much further than recognizing a corner of France.

This idea of uniting all of the Basque Country in one political entity that would be graphically represented by Zapiak Bat (which, by the way, is the coat of arms at the top of our website) is not unheard of in the Northern Basque Country. Labourdian Dominique Joseph Garat, who was twice Minister of Justice during the French Revolution and ambassador for Napoleon, proposed this in 1803 (that is, just twenty years after the abolition of Basque freedoms north of the Pyrenees). (If you’re looking for more information about all the political movements that have been and still are working for the unity of all Basques, you need to see this.)

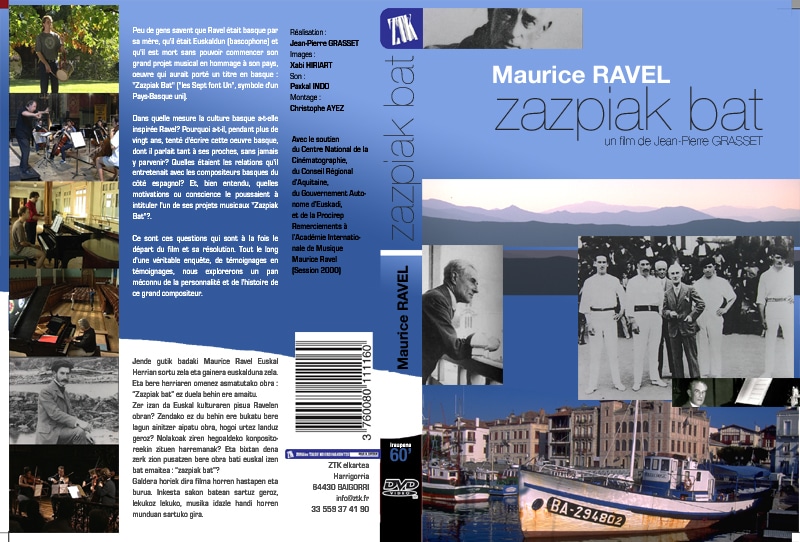

All this came about because, as we were writing an entry about a Basque traditional music group, Kalakan, on their website, we found among the discography and videos, a documentary titled “Maurice Ravel: Zazpiak Bat.” It’s a work that defines itself as a great way to get to know one of those facets of Basque history that are hidden by our history books that want to make our people passive actors in their own history and in that of the world.

Here’s that reference, should you be interested.

ZTK Diskak – 5/2011 – Euskadi

Maurice Ravel : Zazpiak bat

Peu de gens savent que Ravel était basque par sa mère, qu’il était Euskaldun (bascophone) et qu’il est mort sans pouvoir commencer son grand projet musical en hommage à son pays, oeuvre qui aurait porté un titre en basque : “Zazpiak Bat” (“les Sept font Un”, symbole d’un Pays-Basque uni).

(Continue)

——————————-

As an extra, we’ll leave you with a performance of Ravel’s “Bolero,” with two pianos and a txalaparta. Sisters Katia and Marielle Labèque are at the pianos and two of the members of Kalakan are on the txalaparta. Enjoy!

Last Updated on Jul 14, 2022 by About Basque Country