Mark Bieter is an attorney and writer in Washington, D.C. He is the co-author of An Enduring Legacy: The Story of Basques in Idaho. Follow him on Twitter @markbieter

WHENI attended the Jaialdi 2015 international Basque festival in Boise, Idaho a couple weeks ago, it occurred to me that right now could be the best time in world history for Basques. The current Basque president was there. The former Basque president was there. Basque representatives to Spain’s central parliament and dozens of other Basque government officials were there. All of them had been elected by Basques. That wouldn’t have happened if there had been a Jaialdi 1975.

During Jaialdi 2015, the ikurriña flew over the Idaho State Capitol. It flew over Boise City Hall. It flew over the Grove Hotel and the entrance of Pengilly’s Saloon. It was painted on faces, t-shirts, and bags. It was tattooed on shoulders and ankles. That also might not have happened if there had been a Jaialdi 1975.

Jaialdi 2015 opened on the Basque Block in central Boise with a concert by the Grammy-winning musician Kepa Junkera, who wasn’t playing in Boise but streaming live from the top of the 40-floor Bilbao headquarters of Iberdrola, a Basque company that is now one of the biggest utilities on Earth. The camera flew over the many buildings put up in Bilbao in recent decades, including the Guggenheim Museum, which is now one of the best-known buildings on Earth.

For Kepa Junkera and his band, the concert started at 3 in the morning Bilbao time. You couldn’t tell that in Boise, where it was 7 in the evening. But you didn’t have to be in Boise to see the concert. You could watch it anywhere in the world. Those who actually were in Boise posted pictures of the massive crowd on Instagram for their friends in the Basque Country to see.

And yet if you were at Jaialdi, it seemed few people remained in the Basque Country. Most of them had left for Boise. Thousands made the long trip from Mundaka and Gasteiz and Donibane Garazi and everywhere else in the seven provinces. Some wore Athletic Bilbao jerseys as they watched their team play Inter Baku in the first round of the Europa League, which was also shown live from Bilbao in the Basque Center.

There were Basques from California, Australia, Mexico, Wyoming, Venezuela, Argentina, the Philippines. There were Basques from five continents.

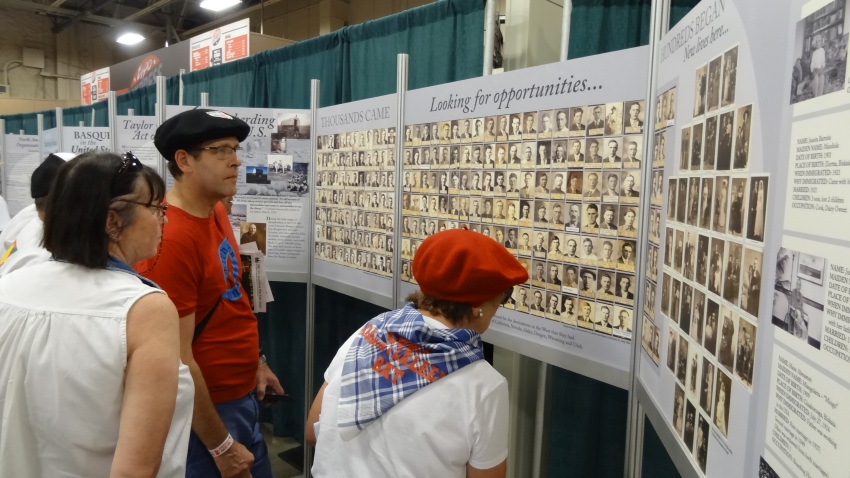

That may not be surprising to the thousand who were there. It was to me. Boise is my home town, and I’ve been to all seven Jaialdis since 1987. But I’ve lived away for many years, so it might be a little easier for me to acknowledge the trip they’ve made and the shock they might get when they arrive. Boise is the capital of Idaho, a state that wasn’t admitted to the union until 1890, when it was a frontier city with dusty streets, suspended in the high desert and surrounded by mountains. It’s still the most remote urban area in the United States. That’s in 2015. Imagine a young Basque man arriving at the Boise train depot in 1903. There was nothing ahead but years of sheep and loneliness.

There was no loneliness at Jaialdi 2015. Everything was crowded. Everything was more crowded than anyone thought it would be. It was a big topic of conversation all week: Look at all these people from everywhere.

Jaialdi began to form its own reality. You turned a corner and came face-to-face with giant puppets three times your size in an alley by the garbage cans, towering in the hot blue sky and preparing to perform. There were four languages swirling around. There was a man in an arena in front of 5,000 people, hanging in mid-air by a rope, trying to pull up a bale of hay as many times as he could.

Things in the Basque Center filled up. Bar Gernika at the other end of Basque Block filled up. You’d find yourself back to back with somebody from Idiazabal or Reno and start talking. Then out of nowhere a triki trixa group would take over the room. Conversation stopped. Nobody minded. That was why they were there in the first place.

At night, there was a full moon, fat and orange over the dry hills. It was there above the crowds all night. It stayed there in the horizon as the sun rose on the other side of the sky for those who pulled a gau pasa for many nights on the Basque Block and may still be there now.

People have met their future spouses at Jaialdi. I know that because my brother met his future wife at the last Jaialdi. You got the feeling that others were meeting their future spouses at this Jaialdi.

The Basque National Party, founded in Bilbao in 1895, celebrated its 120th anniversary on July 31 in Boise. They threw a party. The well-followed, California-based blogger Hella Basque threw a party. Pretty much everyone threw a party, for their relatives from Bizakaia and everywhere else. There were parties going on that you didn’t even know about. There was more going on than you could attend in a month. You would have loved to attend them if you hadn’t been watching the pala tournament in the 101-year-old Anduiza fronton on the Basque Block.

There were presentations on the 1615 massacre of Basque whalers in the Icelandic fjords. There was a presentation on Basques in the Pacific. There was a fascinating presentation on Basque shipbuilding and exploration. It ended with this thought: Centuries ago, when the first English ships were setting out to explore the world, the last Basque exploration ships were headed in, having already explored it.

You heard Euskera everywhere. Iñigo Urkullu, the Basque-speaking lehendakari, visited the kids at Boise’s ikastola, the only one outside the Basque Country. There were signs in coffee shops and stores in Boise that said Ongi Etorri. You could probably survive only on Basque for the whole week in a state whose legislature had declared English to be the official language.

When you live away from the Basque Country, you have to take Basque culture in whatever small doses you can get — a weekend festival, a friend’s visit, a Basque movie that finds its way to an art house. Jaialdi is more than a small dose. It’s like a huge shot of adrenaline. You could see it especially for kids no matter where they came from. Nobody could say what event or moment might have an impact on them. But there was definitely an impact.

For Basques in Euskal Herria, I think Jaialdi is like a thermometer. They get a chance to step away and measure where they are. It’s too early to say, but I have the feeling that I was probably wrong with my first impressions: 2015 might not be the best time for Basques. At Jaialdi 2065, things might even be better.

The only problem with Jaialdi is that it’s now so big you don’t get to see everyone you’d like to. I only saw a fraction. All week, I had wanted to see one person in particular. He was a Basque friend from Mexico City I first met at Jaialdi 2005. I didn’t see him again until Jaialdi 2010. Since I hadn’t seen him yet this year, the event didn’t feel complete.

Then, in the waning moments of Sunday night, I finally ran into him in the Basque Center. We were both five years older than the last time, but it was like no time had gone by. I told him, “Miguel, we have to stop meeting like this.”

He gave me a serious face. “No we don’t,” he said. Then he stepped back and stretched his arms to all the people in the packed bar. “Why can’t we keep meeting like this forever?”

Last Updated on Dec 20, 2020 by About Basque Country