Murchante – Ribaforada

In the last century, the social conflict in Murchante was marked by the lack of irrigation coupled with the small size of the city limits. The division of land of the Cierzo Mountains did not satisfy the townsmen, and there were lawsuits with neighboring towns. The border of Urzante was also a matter for lawsuits. In 1919, 400 dayworkers went on strike demanding better pay and a shorter workday. The Caja Rural savings institution, founded in 1908, was the support for the landowners to organize and remain united against the demands of the workers of the land.

The arrival of the Republic promoted workers’ associations, and in May 1931, the UGT labor union was born in Murchante out of two associations, the Society of Different Trades and the Society of Land Workers, both located at number 22 Triunfante Street. The presidents of UGT were Amancio Aguado, José María Magaña, and Antonio Pérez, and in 1932, it reached 175 members. Similarly, the Socialist Republican Center at number 34 Main Street was born, with Julio Orta as president. At the end of 1935, the Republican Left was born, at number 22 Paz Street, and its president was Francisco Rosel.

The corralizas of La Torre and Las Hoyazas were the goal UGT set itself to ensure were returned to the dayworkers, as well as replanting pine trees, which was carried out. The La Torre corraliza, according to mayor Manuel Martínez, went head-first against an agreement with a farmer from Tudela. Given the city’s no, several townsmen took matters into their own hands, and in 1932, armed with a bravan and several horses, Ángel Pérez, Generoso Ochoa, brothers Pedro and Benito Arraíza, and Antonio and José María Magaña went to the corraliza.

After tilling the land for several days, the farmer from Tudela complained to the mayor, and he in turn to the Civil Guard. A sergeant with four mounted men violently attacked the dayworkers. The Governor, on hearing the news, ordered an investigation. All parties involved were convened to clear things up, and a Civil Guard captain acted as intermediary. The dayworkers and the Mayor, with two Owners’ Association representatives, met and it was agreed to divide the land up. The mayor was given three months to do so, and each parcel was divvied up to 3,000 m² (0.75 acres) parcels.

The influence of parish priest Pedro Legaría is key to understanding why 200 townsmen with all types of weapons stood guard all night against the arrival of the Jesuits from Tudela because of the news of convents being burned. The Governor’s order to withdraw crucifixes from schools alarmed a group of the town’s Catholic mothers such that they attacked the school and the teachers, especially the girls’ teacher. The two leftist councilmen complained about how long it took the Civil Guard to come when called.

After the Fascist Military Coup, Hilario Simón took the reins at the City Hall and created a War Committee, made up of himself and Manuel Martínez. Hilario Simón was also the head of the local Falange. He made many decisions, including firing Ángel Martínez Simón as forest ranger, because he was considered to be opposed to the ideals of the Movement. On November 20, Roque Jarauta, Hilario Chueca, Antonio Pérez, Mauricio Simón, Ricardo Rosel, Julio Orta, and Genaro Ochoa are arrested. They didn’t even spend one night in Tudela jail, as they were immediately killed in Fustiñana.

The tobacconist’s shop, until then owned by Julio Ortoa, was taken over by Luis Fernández, the requeté chaplain who had directly participated in the shootings of the prisoners from Tafalla at the Monreal Mill. A few days later, a large group of townsmen is locked up in the schools, where they will stay for three months, while family members took them food. Pedro Magaña and his son José María, Manuel Simón, Isidoro “Tío Caracol”, Ángel Baroja, Genaro “Rinconero” Ullate, Hermenegildo Irujo, Constantino Lorente, Ernesto Murillo, Gregorio Soria, Apolonio “Cartucho” Ochoa, Isaac Ochoa, Francisco Simón, Ángel Pérez “Costillares” were also taken prisoner.

Others signed up for the national front and went over to the Republican side, such as Antonio Magaña and Simón “Chambero”, Pedro and Benito Arraíza (“Los Obispos”), Pedro Simón, and Cirilo Martínez; Ignacio Calahorra was shot while trying. Five local religious were killed on the Republican side: Teófilo Casajus, brothers Lorenzo and Guillermo Alduán, Manuel Martínez, and Francisco Simón. Many townsmen were forced to work for free for those who were on the side of the military uprising, and Private Gregorio Martínez was in charge of looking for workers to do that forced labor, which was carried out under surveillance. There were three owners who did not take advantage of the slave labor, either by letting them go or paying their wages, and these were Félix Aguado, Leoncio Hernández, and Apolonio Crespo. No women had their hair cut. There was only one attempt, with the women who had flown the Republican flag on May Day, with Rosario Simón, María Brun, and Felisa Ullate, but in the end, no one was shaved.

Ribaforada

The Lodosa Canal had just been built at the end of the Republic, and the common land was once again being demanded by the least fortunate. Since 1901, the City had been giving permission to the farmers to feed their cattle on common land in the Mountain, and even on private lands. The arrival of the Republic gave an extra push to the demands for Land, and the large landowners, Ochoa, Sanz de Ayala, Arriazu, Oliver, López de Goicoechea, and others, found their privileges in danger.

The April 12 elections were challenged by the left, and when they were repeated, the right got five councilmen and the left, four. It must be said that the monarchists on the right had dressed up as republicans. The mayor chosen by the right was Nicolás Gómez. The legislative elections on June 26 unmasked the right, and 84.64% of the votes in Ribaforada went to the left.

The City of Ribaforada, with a rightist majority, unconditionally sided with the Basque-Navarrese Statute of Estella: they changed street names, introduced the color purple to the flags and tobacconists’ signs, and the statue of the Blessed Heart of Jesus was removed. Also, the use of more than 7,400 robadas (660 m², 0.16 acres) of common land owned by Concepción Lacar, a 200-robada Carrizal property, the Carrascal e Isla Soto, and the use of the grasses of the Mountain were also demanded. Two teachers were hired to meet the growing educational needs.

The representatives of the Land Workers’ Society, José Domínguez and José Diago, sent a petition to the Provincial Government to officially allot the El Juncal property to the Society, based on the fact that the lands had not been worked for 40 years. In March 1933, the collective exploitation of that land began. In Ribaforada, in addition to the Socialist Groups, there was also a group with Libertarian ideas that worked closely with the socialists so as not to break up the left. José Zardoya introduced anarchical socialism, and Domingo “El Fraile” was its main proponent. In February 1936, the right won with 402 votes, to the left’s 326.

The Fascist Military Uprising meant the whole City Government was fired. Salvador Arriazu was named by the military insurgents. One of the first agreements of the insurgent city government was to expel 25 families from Ribaforada: Manuel Robles, Juan Melero, Antonio Bernal, Miguel Bernal, Guillermo Lore, Antonio Benede, Iñigo Pardos, Gregorio Vallejo, Juan Cruz Tobajas, Manuel Mateos, Francisco Berdejo, Gregorio Andreu, Datirio Carrión, Lucio Gutiérrez, Agustín Benede, Celedonio Martínez, Rufino Martínez, María Marín, Luis Martínez, A. Corral, Julián Martínez, Andrés Pinzoles, Antonio Mesa, Juan Chavarri, and Joaquín Robles.

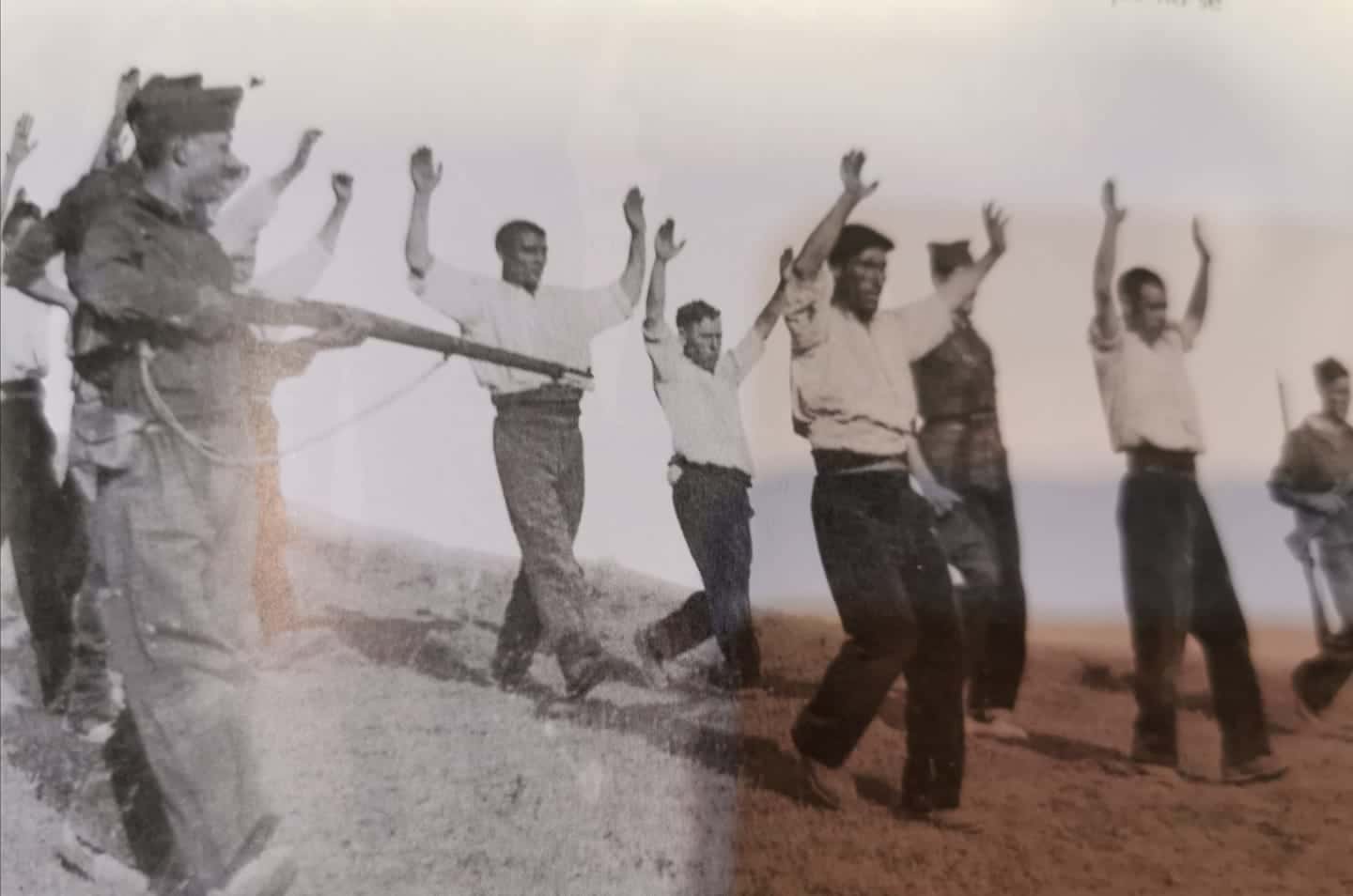

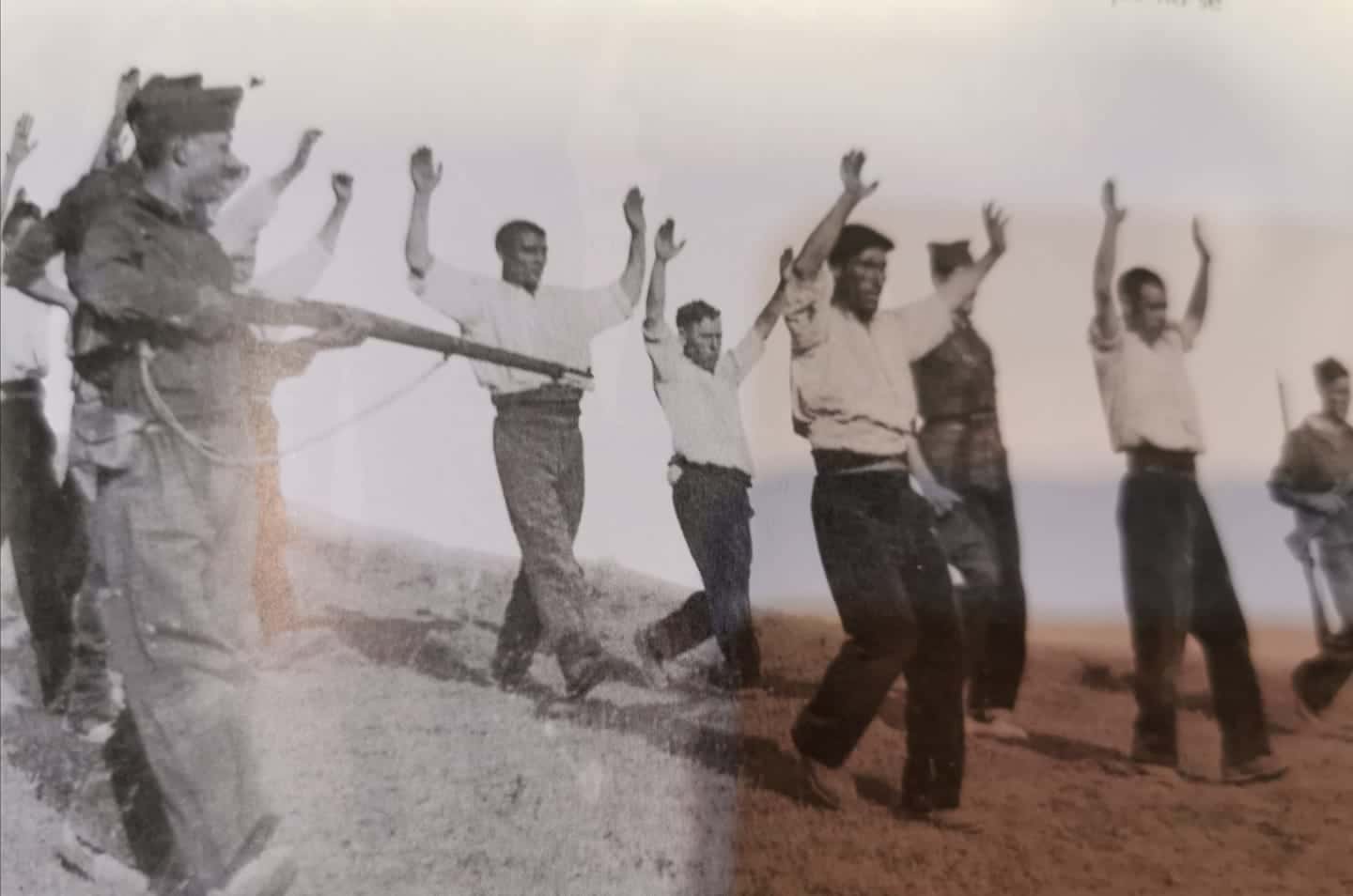

On July 19, 1936, the Civil Guard, with the help of several townsmen, took Ribaforada and started massive raids, making so many arrests they filled up the jail, the meeting room, the butcher’s underneath the City Hall, and the schools. That same day, Babil Ayensa was killed with one shot. The prisoners were beaten daily, and Tomás Galindo was killed in one of them. His body was disappeared and has never been found.

The first removal from the prisons took place on July 24, and twelve men were taken to Bocal, loaded onto a boat, and shot and thrown into the Ebro River. One of those who were to be killed was not killed that day because he owed 30 pesetas to the priest, Juan Guillén. In this and later “cleanses”, the “Corneta” played an active role. Brothers Jiménez Ducas, Antonio Bernal and his son Félix, Felipe García, Antonio Marques, Cesáreo Pérez, Andrés Ruiz, and Ángel Villafranca were thrown into the river. At least six locations in Ribaforada were attacked and sacked: the dance hall, the cinema owned by José Domínguez, murdered in Fontellas, the homes of Cesáreo Pérez, Luis Santos, “las rojas”, and Bruno Enrique, murdered in San Martin del Moncayo.

Teachers José María Escribano Santos and Carmelo Caballero were indefinitely suspended without pay. Many of those arrested were taken to Tudela, and at the beginning of August, were murdered in Fontellas. Brothers Gochicoa and Fermín Cantón, Aniceto Corral, Mariano Navarro, Juan Melero, Luis Santos, and Miguel Castillo were taken to be killed; the latter told his murderers: “If you believe in God, kill only me and let the rest of these people go.” Some tried to flee and were captured and killed: Felipe Chávarri was killed in Murchante on August 5, along with Bruno Ortigala. José and Pedro Diago hid in the Bardenas and were killed in Cortes. José Corella and José Blasco were also killed.

Thirteen people more were murdered: Pío Castillo, Santiago Gil, Antonio Mesa and his son José Murillo, Francisco Ortigosa, Tomas Pantaleón, the Robles brothers, Francisco Orta, Ignacio Sánchez, Gregorio Vallejo, and Ángel Zardoya.

Those women who are known to have had their hair cut were: María Cantón, Teresa Cantón, Cándida Ducar, María Jiménez, María Huguet, Josefina Corral, Casilda Murillo, Paquita González, Marian Gos, Teresa Enrique, Ángeles Aguado, Flora Castillo, Dolores “La Motola” Murillo, Maruja Blanco, and Sabina Melero.

Testimony in the book “Navarra, de la esperanza al terror, 1936”:

“The falangists went from house to house, taking women of all ages, from 13, which is how old I was, to some who were 50 or older. I think we spent over 80 days under arrest. They took us to the City Hall and up to the Meeting Room. There were two barbers there, one of them leftist, sucking it up. They forced them to leave our heads like the palm of our hands. The Plaza was full of curious people who laughed and insulted us when we left with our heads shaved. One of us went out to the balcony and said, ‘Have you seen me from the front? Now look from the back!’ and she turned around. The next day, they made us go the Plaza again. They read a piece of paper accusing us of everything, and then farcically forgave us. They made us swear to the flag and sing the ‘Cara al Sol’. After that, we had to parade through the whole town to the beat of the music following us. They also took us to the station when the train went by. The married men wanted to take advantage of us, but some of the single men wouldn’t let them, saying that maybe someday they would want to marry one of them. The single men wouldn’t let them, thinking that.” (M.J. Ribaforada)

Last Updated on Jan 16, 2021 by About Basque Country