This article was translated by John R. Bopp

Vince J. Juaristi is a Basque-American born in Elko, Nevada who has a company in Alexandria, Virginia, and who has written about the Basque diaspora in the US, and who is becoming quite a role model here at the blog.

The Elko Daily has just published another article, the third, of his, dedicated to Basques and their relationship with the US. All of them have been written to thanks to Basque culture being the guest of honor at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival 2016 being held at the end of June and beginning of July at the National Mall in Washington, DC.

This third entry remarks on an especially close topic to us, that of the Basque resistance to totalitarianism in the 1930s and 40s, specifically about one of the key elements of the Comète Network which, during the German occupation of Europe in the Second World War, helped people persecuted by the Nazis to escape. We’ve blogged about it on many occasions.

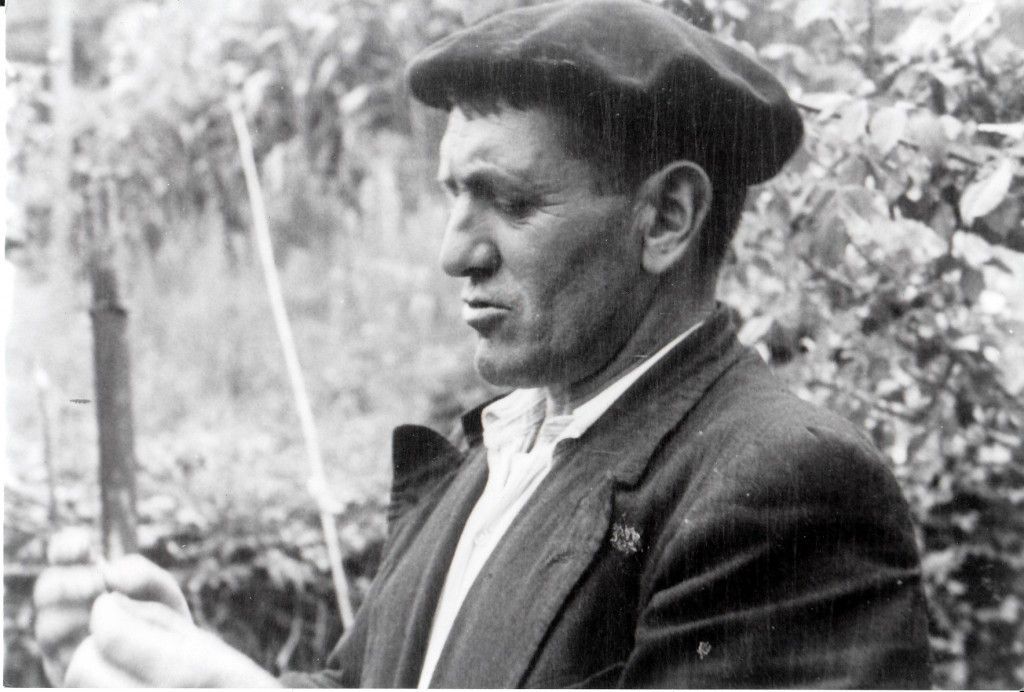

This key element is a man: Florentino Goikoetxea. A farmer from the Lower Basque Country, he fled Francoism to the Northern Basque Country, and during the Nazi occupation, he was one of those in charge of getting persecuted people across the border, and thereby escaping the forces of occupying Germany, and the forces of Franco, which governed the territory south of the Pyrenees after the Spanish Civil War.

That simple man was one of the key pieces to the anti-Fascist struggle, for which Basque nationalists and republicans were on the front lines. Once again, we recommend reading the article by Juan Carlos Jiménez de Aberasturi Corta, called “Los vascos en la II Guerra Mundial: De la derrota a la esperanza“ (“Basques in World War II: From Defeat to Hope”), where he describes that struggle. The work also cites the man who is the protagonist of our Elko Daily story today.

When this man was honored by the British for his bravery and courage with the Cross of St. George, he was asked, “What do you really do?” His answer: “I’m in the import/export business.”

As we commented in an earlier entry on the efforts of Basques in North America in the struggle against Fascism, we’ve collected many stories over the years of those who, in one way or another, fought in that global war. We’ve talked about the Southern Basques who joined the fight against Fascism, and those who have honored them. We’ve cited the heroic acts of civilians far from the front lines who performed necessary tasks in the war effort or to save innocent victims, like those Basques who participated in the Comète Network in the Basque Country. We’ve also blogged about those Basques who used the Basque language to “encrypt” messages in the Pacific Theater. We’ve even mentioned the aid work done for the Jewish Population of Europe during the war and the years immediately following.

It’s an effort that is unfortunately largely unrecognized, individually and collectively.

That’s why the work of Mr. Juaristi is so important, sharing and reclaiming that part of our history.

As a finaly note, we’ve loved to see how Mr. Juaristi and we coincide on the image used to define the role of the Basques in the Comète Network. In April 2015, we wrote this about the role of the Basques in the fight against totalitarianism:

Just like the work of the Basque ‘mugalaris’ turned passed them into the “tail of the comet”, helping downed pilots or persecuted Jews being taken to safety thanks to the Comète Network.

Elko Daily – 5/372016 – USA

Intertwined: The Tail of the Comet

Florentino Goicoechea (Basque: Florentino Goikoextea) lived in a 24-mile stretch of land between Hernani, Gipuzkoa, Spain, and Ciboure, France. He grew up in a small farm house without electricity or plumbing, hunted antelope and big-horned sheep in the hills south of San Sebastían, and fished the Bidassoa River that traced the Spanish-French border. He knew the Pyrenees that ran like a zipper from the Bay of Biscay to the Mediterranean with more than 50 alternating teeth peaking above 10,000 feet. He knew the sounds of night and day and the animals that growled, chirped, snarled, or hissed in the dense foliage and jagged rock along the high mountain passes. He had no formal schooling, only the knowledge afforded by these 24-miles, but it was this familiarity most of all that came to serve America and the Allies during World War II.

(Follow) (Automatic translation)

Last Updated on Dec 20, 2020 by About Basque Country