On November 8, 1948, the first issue of Oiga! magazine, the greatest work of journalist and author Francisco “Paco” Igartua, was published. We have written a great deal here about this magazine, and we recently celebrated the centennial of the author’s birth. But November 8th was when Oiga, the political analysis journal that would make history in Peru, got its start, and even today, 75 years after its birth, it’s still a role model for journalism in Peru. At the time, Igartua was 25, and he already knew what it was like to go to jail for exercising his right to free speech.

The Birth of Oiga

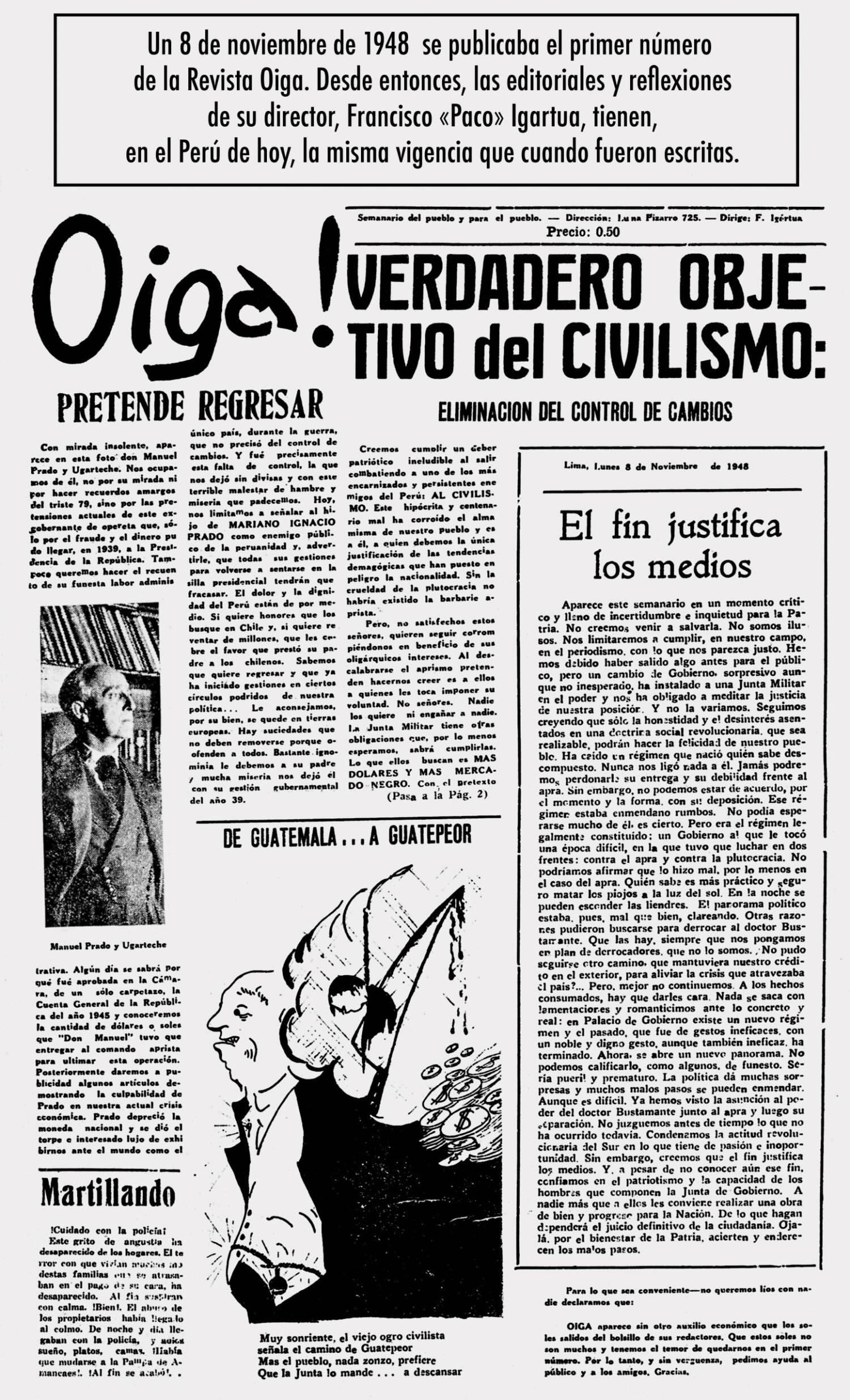

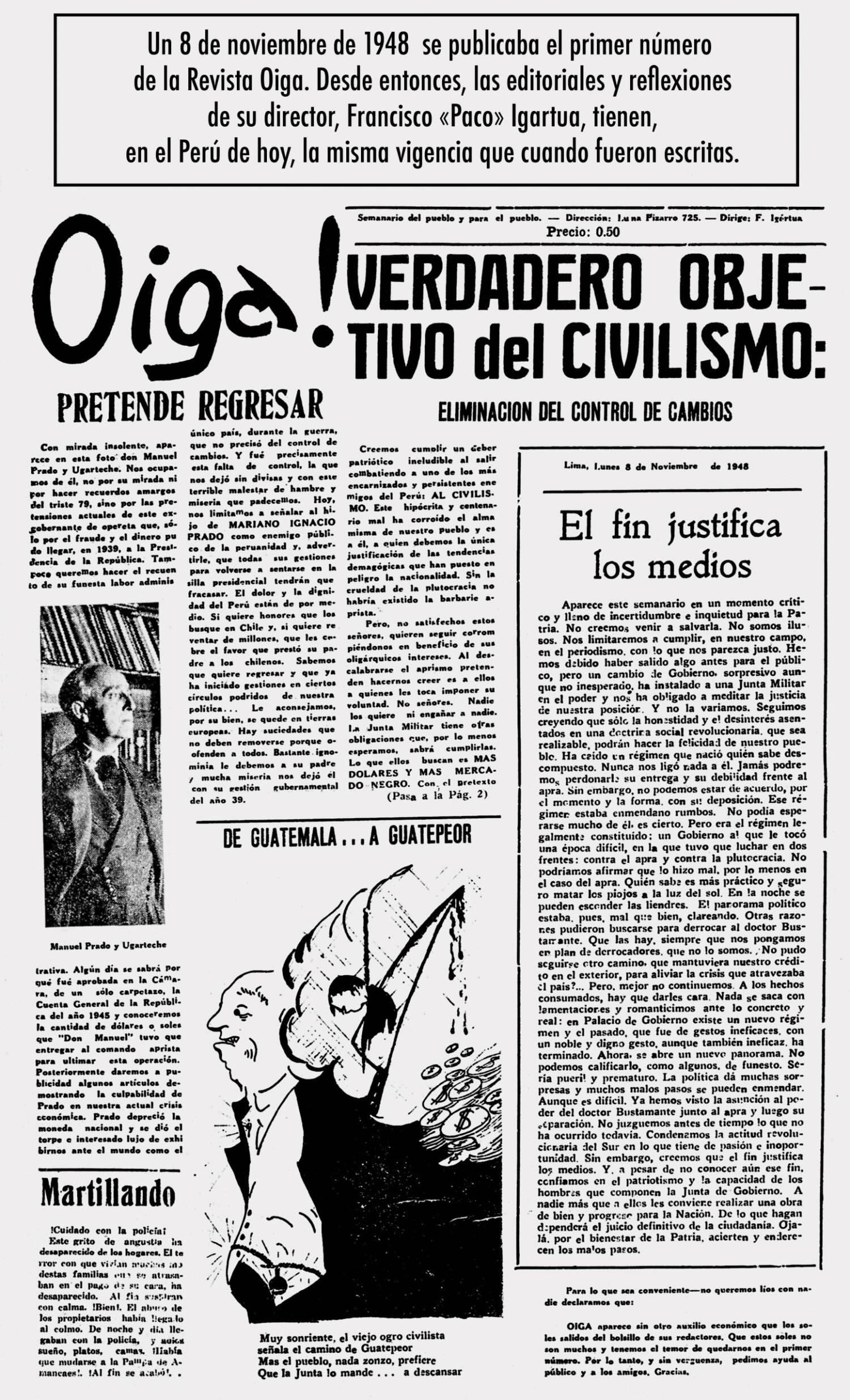

The weekly Oiga! was the consequence of the coup that General Manuel A. Odría led on October 27, 1948 against President José Luis Bustamante y Rivero. It is therefore not at all strange that in the first issue, the founding editor wrote, “This journal makes its appearance at a critical moment that is fraught with uncertainty and unease for the country.”

But only three issues were published, as its director was jailed just four weeks after the first issue. That first issue was followed by two more, and then its closure, at the orders of the Odría dictatorship.

That finished off the first stage in this publication’s life. It was so short that it is often not regarded as even counting as a stage.

In his book “Siempre un extraño,” Igartua mentioned a story that so far has not been retold by his biographers: when arranging the financing for the first issue, Peruvian journalist and publicist Doris Gibson Parra del Riego selflessly participated, as Igartua himself recalled:

“That morning, on the first or second of November, 1948, around midday, Francisco displayed a pamphlet in the doorways explaining his reason for publishing a weekly, which would shout out his generation’s protests against Bustamante’s coup and its rejection of the dictatorship that had just taken over the country. But Francisco didn’t have a penny. At the table were Sérvulo and Doris Gibson, Guillermo Ugaz, Juan Ríos, Carmen Sosa, and someone else. Francisco explained his projects and his lack of funds. Doris Gibson immediately volunteered to help him get them. And, standing up, she walked over to the other side of the plaza, to the doors opposite, to Chez Victor, where she was expecting to meet Armando Revoredo, Bustamante’s last Prime Minister, who had just been in prison. A short while later, Doris returned to the table at the Café. She brought with her two thousand soles for Oiga, Francisco’s project. The thousand that were lacking were also found by Doris Gibson for Francisco, with some solmenity and the signing of a symbolic document, from Pechitos Bustamente. And that is how Francisco’s first personal newspaper, Ogia, was born.”

First Exile

As is easy to imagine, this publication was not to the liking of the Odría dictatorship, so its closure was guaranteed. But even more than that, the dictatorship disliked that in October 1950, Igartua took over as the director of Caretas magazine, which had been founded by himself and Doris Gibson Parra.

It disliked that fact so much that in 1952, it decided to deport him to Panama. From there, Igartua traveled to Chile, only to then, shockingly and without the military government’s authorization, return to Lima. There, he took refuge at the daily El Comercio, from which the régime tried to take him out by force, but the journal’s director, Luis Miró Quesada, refused. After a great many negotiations, Igartua was allowed to stay in his country, and to once again take over the direction at Caretas.

The Return of Oiga, the Second and Third Stages

In 1962, he left Caretas behind in order to reactivate Oiga, this time without an exclamation mark, and turn it into the leading political analysis journal in Peru. In this time with Igartua at the helm, as he was the chief editor, he chose and supported different candidates for president.

One of those was Fernando Belaúnde Terry, whom he backed in his 1962 presidential campaign, only to go onto analyze his government and be very critical of it. This is because Igartua was always faithful to his positions against corruption and in defense of democracy, social justice, and freedom of the press.

This led him to supporting political leaders who seemed to coincide with his views, but to then analyze their leadership and criticize them once they achieved power and forgot their principles.

During the Belaunde government, Oiga started its third stage, when it dropped the “newspaper” format and adopted the “Time magazine” format in 1965.

In 1968, given the impasse in the Belaunde government at the hands of the APRA and the Odría supporters, the military, headed by Juan Velasco Alvarado, launched a coup d’état, justifying it on the need to push forward a plan that would get the country out of the crisis situation it was in.

After the coup, the commanding generals of the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force constituted the Revolutionary Government of the Armed Forces of Peru, whose state goal was to increase social justice by nationalizing strategic production sectors (such as banks, oil, and exporting industries) and leading a profound agrarian reform.

Igartua, and therefore Oiga, supported the reform process, but defended the need to call elections for a Constitutional Assembly, and the need for a free press.

The Second Exile

Igartua’s protests via Oiga magazine against the Velasco government’s control of the media brought with it his exile to Mexico in 1974, where he resided until 1977. That is to say that Igartua was exiled by both right-wing and left-wing governments. As different as their ideologies may have been, both governments shared an anti-democratic position, and therefore could not abide the freedom of speech or of the press.

He could have taken refuge in Chile, which had just been taken over by Augusto Pinochet, who was diametrically opposed to the principles Velasco said he followed, but no, he chose Mexico. This was the same Mexico that took in the Chileans who were fleeing the Pinochet coup’s repression and who, like him, were fleeing another, contrary type of repression that was represented by Velasco. In Mexico, in recognition of his quality as a journalist, he ended up being named the director of the Sunday Supplement at the daily Cadena Sol. This fact is quite extraordinary, as it is not at all usual for a non-Mexico to be leading a prestigious publication.

Igartua was in Mexico at a time of great cultural, literary, and artistic vitality in general. There, he lived with some of the most important Latin American writers and artists. With them, he not only had a close relationship, but he also collaborated with them via the Sunday Supplement. One important task still remains to be researched in Igartua’s life: researching his work and relationships during the three years he was in Mexico.

As a prelude to that work, and thanks to the work of Josu Legarreta, two articles Igartua penned in Mexico were brought to light. They are some of the few who were actually penned by him there, and we’re sure it’s no coincidence that they discuss two matters that are deeply important to a democrat who defends liberty, and to a Basque like Igartua.

We, on this anniversary of Oiga magazine, bring them to you, because we believe that they reflect the spirit that guided the entire life of this Peruvian who felt deeply Basque.

His View of Franco

In the one dedicated to another dictator, a type of character that he knew very well thanks to his life experiences, he refers to the death rattles of Franco’s regime and the different horizons that emerged after the disappearance of his dictatorial regime. In the article, he demonstrates a good knowledge of what happens in that “Kingdom of Spain in a state of regency” (as the dictator himself defined it).

He speaks of the movements of groups opposed to democracy; of the resignation of Lieutenant General Manuel Díez-Alegría, who wanted little to do with the most intransigent followers of Franco, from the Chiefs of Staff; and of the Basques as the only ones within the Spanish State who were clearly opposed to the regime imposed by the dictator.

In his lengthy article, if one reads between the lines, one can find a response to those who defend totalitarianism by shielding themselves with the excuse of “what’s good for the people.” He does so by quoting Mario Soares and his idea for socialism that respects democracy, freedom, and social justice, juxtaposing it with those who believe that between democracy and social justice the former can be sacrificed for the sake of the latter. Perhaps while writing it, he was thinking of the case of Velasco Alvarado.

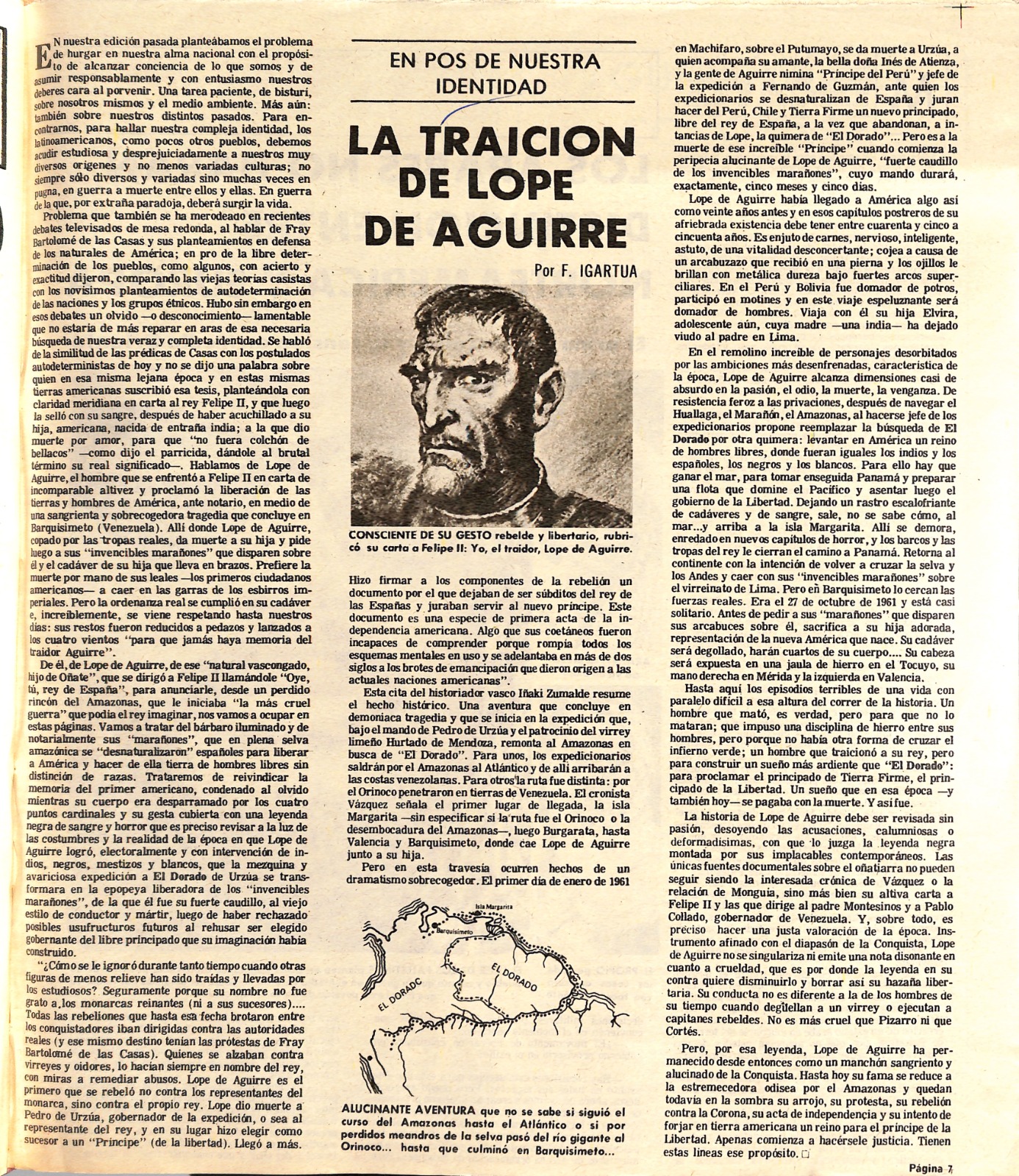

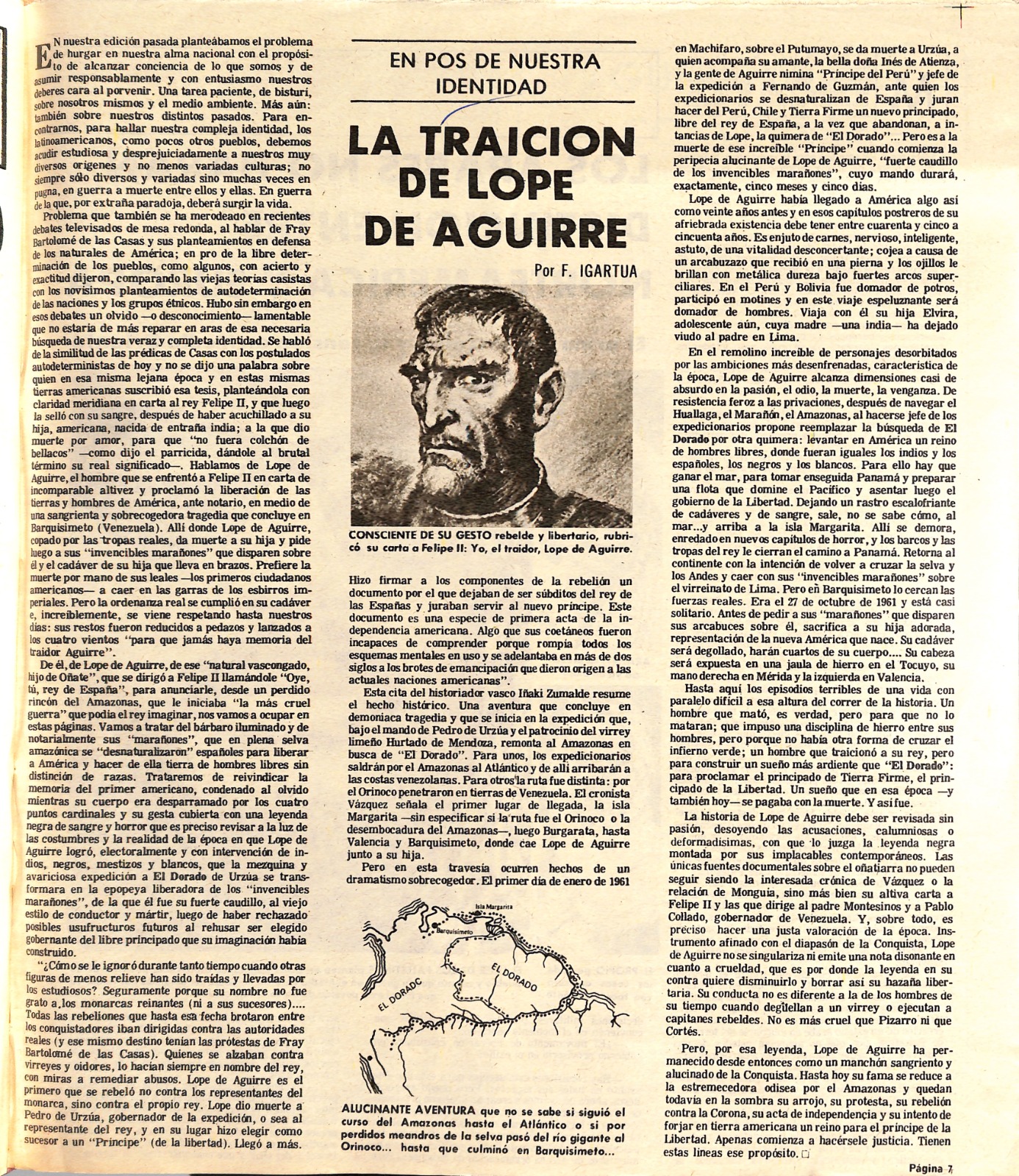

Lope de Aguirre, the first declaration of independence in the New World

The second article, about Lope de Aguirre, or “The Madman” as he was usually called, or “The Traitor” as he called himself in his extraordinary letter to Philip II in which he declared the independence of the Spanish colonies way back in the 16th century, is not only a lesson in analysis or history; it is also the vindication of a man, a Basque man, who had been forgotten and vilified.

On Margarita Island and in other places in Venezuela, even today (or at least up until a few years ago), misbehaving children were still told that the boogeyman Lope de Aguirre would come for them. That shows the power of the black legend imposed by the colonial powers, whose legacy has managed to survive even in the Venezuelan Republic that threw off the colonial yoke created by the same people who demonized Lope de Aguirre.

In his article about Lope de Aguirre, Igartua did the same thing that the Congress of the Basque Communities Abroad did years later: remember and vindicate a forgotten historical figure, introducing him with all his value and importance.

In the first Congress of Basques Abroad, held in Vitoria in 1995, he vindicated members of our Brotherhood of Our Lady of Aranzazu in Lima before all the representatives of the Basque communities abroad and other Basque institutions.

He did so by recalling that the first groupings of Basques that were organized in the New World were not born in the 19th century, as claimed by those who did not have a global vision of the Basques in the world, but rather in the 17th century. The brotherhoods and guilds of Aranzazu, born to defend the interests of the Basque community, served as a nexus for a network of support for the Basques throughout the Kingdom of the Spains. Of all of them, the one in Lima, founded in 1612, was the first.

Return to Peru: Fourth and Fifth Stages of ‘Oiga’

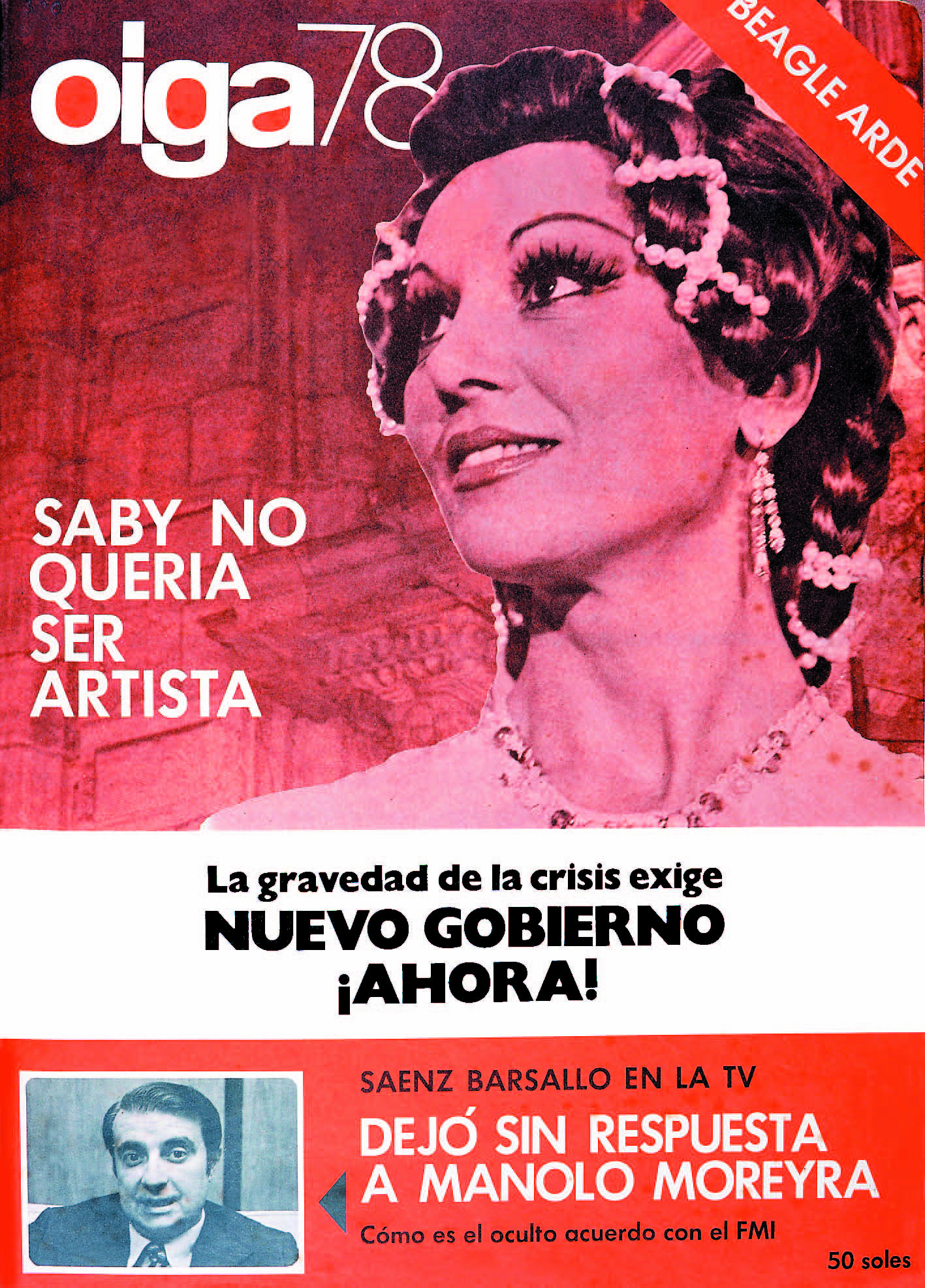

On returning to Peru, he started the fourth stage of Oiga in 1978, bringing back the tabloid format, and using the new masthead Oiga 78.

In 1980, with the start of the second Fernando Belaúnde government, Oiga began its fifth stage, by bringing back the Time style and becoming the weekly journal with the broadest coverage. It also included new sections not devoted to current events, but which were a bit more like a lifestyle section.

What never wavered was his coherent position in defense of the principles that had always guided him: the fight against corruption and the defense of democracy, social justice, and freedom of the press. That is, he continued to denounce the excesses of the political and social elite of his country.

With great effort and no small degree of hardship, Oiga remained at newsstands throughout the Belaúnde and Alan García governments, as well as through the first five years of the Alberto Fujimori government, until the latter’s political and economic pressure, applied after he became a dictator via a “self-coup,” chocked out all opposing press via abusive taxes, and Oiga was closed. This closure ruined Igartua financially, as he honored all his debts with workers and suppliers.

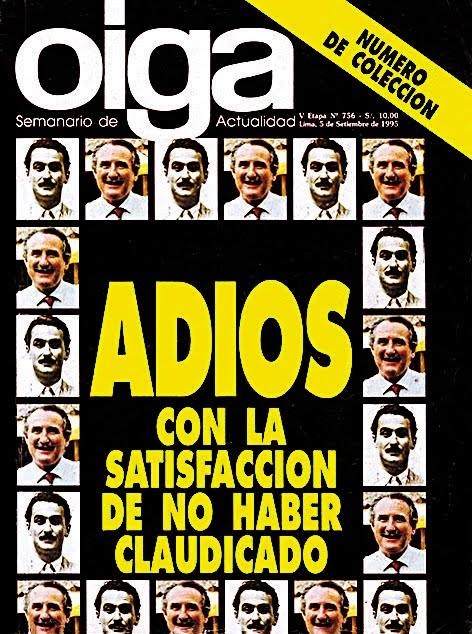

The End of Oiga and Its Farewell

Perhaps if he, like others, had abandoned his principles, the magazine might have survived with him at the helm. But Igartua wasn’t that kind of journalist, or person.

The last issue, number 756, was printed on September 5, 1995, with the title “Farewell with the satisfaction of not having given up.” In it, he says goodbye with an editorial that explains the reasons for the closure, but also explaining why he refused to give into blackmail.

As he says in one of his paragraphs:

“Pero ¿qué importa lo ganado o lo perdido en la ruta? Sí me importa morir con dignidad, con la altivez con que vivimos estos últimos 33 años de Historia del Perú.”

But what does what was won or lost along the way matter? It does matter to me to die with dignity, with the pride of having lived these last 33 years of the History of Peru.

«EDITORIAL “Goodbye, Friends and Enemies”

By FRACISCO IGARTUA ROVIRA September 5, 1995

In any farewell, something of our existence goes away, and in each goodbye, we die a little. And since this is a goodbye with greater echoes, the sensation of life being shortened that accompanies my pencil in these lines is greater, even though in my brain, the hope that this goodbye will be but a pause in the long battle OIGA has had to ensure that the citizens of Peru understand that true development can only be achieved when we build a democracy, when we turn this homeland of ours into a state that follows the rule of law, continues on. Why can’t this closure of the fifth stage of this eventful existence of OIGA mean just a pause in the battle? Why must it be impossible for there to be a sixth or even seventh, life, like cats, insisting on the fact that the great economic programs, the brilliant loans, the magic of finance, the overwhelming physical works, the spectacular growth of tourism, will not be real, but rather only appearances, if Peruvians continue to be pushed aside from civic culture, without understanding that meticulously following the law — both by those on top and those on the bottom — is the only solid foundation for true and sustained development?

Unfortunately, though, this is not the future — still quite uncertain — that I’m here to discuss in this editorial. It is incumbent on me to refer to certain events of the present, or rather to repeat what I wrote to my friends two weeks ago: OIGA will appear no more. After 33 years of reaching the hands of our readers every week — except for some interruptions, some short and some long, caused by closures and a deportation to Mexico — this long dialogue that we have maintained with our readers is being stopped.

“Dialogue?” more than one of the OIGA readers who do not love us might derisively ask, and I shall respond by saying with Master Unamuno that, well, no, they may not be dialogues — as useless as those catechisms full of questions and answers — but rather self-dialogues, dialogues with oneself, with the concerns that current events sparked in me and the problems that said current events raised in my conscience.

OIGA will appear no more. It is being closed, we are being forced to silence ourselves, by the harassment that the magazine has been subjected to for the past ten years. I have made this decision in consultation with my closest advisors, mainly Jesús Reyes, who has come with me almost since the day, 33 years ago, when I restarted this adventure at OIGA, starting in November 1948, as my generation’s response to General Odría’s revolt against President Bustamante y Rivero, the man who uselessly tried to get this country of befuddled people to understand the value of democracy, civic culture, the following of the rule of law and not to the strongman of the week.

OIGA is closing so as to not have to prostitute its banners, that is, its ideals that did and do belong to the Peruvians who love civic freedoms, democracy, and tolerance, even as we are intolerant to corruption and the dirty games governments and their authorities play. This magazine’s sin, its greatest sin, was that it knew how to be intransigent with its truth — with what each person believes is true — and along the way, we los friends, contacts, benefactors, and especially friends who at one point found refuge in these pages and whose causes OIGA enthusiastically defended.

But what does what was won or lost along the way matter? It does matter to me to die with dignity, with the pride of having lived these last 33 years of the History of Peru.

I have said that there was harassment, and I could tell of the pressure the printer where OIGA is printed felt — a printer that lost each and every tender it applied for — but I do not want to cause problems for third parties who acted with fortitude until their will to help us was broken. I will therefore speak about harassment without entering into details; I shall leave the word hanging in the air. And as for the tax harassment, I will be more precise, as what I say in these final few pages might help my colleagues in the written press, placed in similar situations to those which have led OIGA to have to say goodbye to its readers.

There is tax harassment, and it is pathetic, that voice of the liberalist fundamentalists, those ayatollahs of Fujimorism, who cry out that there should be no exceptions in the tax law to refer to paper taxes and the sales tax on newspapers and magazines — a sales tax that cannot be passed onto the newspaper vendors — and they shut up, locking their mouths with seven padlocks, when sales tax exemptions are granted to education businesses, or when Stock Market business are freed of it, or when the State does not require this tax — so that they don’t go bankrupt — of the pension funds.

Yes, there is tax harassment against the press, which is made worse in books and in reading in general. It makes reading prohibitively expensive, right in the five-year period of Education, it mocks the most basic rights of those being educated: being able to read freely. (Those being educated are understood to be not only those pre-schoolers in schools but also older ones, who only by reading will graduate in that subject that one never ceases learning in, civic culture.) It is also a cruel joke to maintain taht 18% sales tax on medicines and basic foodstuffs in a country of tuberculosis, starvation, and miserly salaries. “Why?” we repeat as so many other times, “are culture, health, and basic foods so mercilessly taxed but reasons are always to be found to be benevolent with financial speculation, pension funds, and companies doing business with education? Why in the five-year education period of Peru is it made prohibitively expensive to read a book?

And, to finish off this farewell note, I must give thanks, many thanks, to all those colleagues who have publicly expressed their sorrow at the closure of OIGA; especially to the dean of the national press, El Comercio; César Hildebrandt, who moved me so in front of the Channel 9 cameras; María del Pilar Tello, at Gestión; Mirko Lauer, at La República; Juan Ramírez Lazo… I shall not continue naming all those voices of solidarity, both from so many exalted personages — President Belaúnde and Ambassador Pérez de Cuéllar, among others — and from former collaborators and friends to the magazine whom I barely knew, because I’m sure I’ll have forgotten more than I will remember, and I would like for my thanks to be for all equally.

OIGA MAGAZINE ARCHIVES

Paco Igartua continued writing in many Peruvian papers, such as Correo and Expreso. His voice would continue to be heard in his column “Canta Claro”, where he covered economic, political, and social topics.

In addition to his fruitful journalistic career, he also published several books, among which we may highlight Siempre un extraño, the first part of his memoirs, and Reflexiones entre molinos de viento, a collection of his articles.

He was married to Clementina Bryce, the sister of famous Peruvian author Alfredo Bryce Echenique, and with Clementina he had two children.

–

More information:

- Articles about Paco Igartua on aboutbasquecountry.eus

- Paco Igartua on Wikipedia

- Interview with Paco Igartua on Euskonews (2002) (in Spanish)

- Article by Palmira Oyanguren about Paco Igartua on Euskonews (in Spanish)

- Article by John Bazan Aguilar about Paco Igartua on Euskonews (in Spanish)

- “America and the Basque Identity” by Paco Igartua in Euskaletxeak (in Spanish)

Last Updated on Feb 12, 2024 by About Basque Country